HN303 ‘Peter Collins’ was an SDS officer, deployed undercover from early 1974 until November 1977. He infiltrated the Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP), initially in north London, where he became a branch chair. He later gained access to the party’s central committee, one of the organisation’s controlling bodies.

Unusually, from July 1975, Collins was tasked by the WRP to infiltrate the National Front, becoming in effect a double agent, reporting on the NF to both the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) and the WRP.

Collins was born in the 1940s, he is deceased. There is no information about his police career prior to joining the SDS, other than that he joined the police in 1966 and, presumably, had the standard Special Branch training. Post-SDS, he resigned from the police shortly after his deployment ended, to pursue another career.

Two former members of the WRP, Liz Leicester and Roy Battersby, gave evidence to the Inquiry. They commented only briefly on Collins’ reporting, and neither recalled the SDS officer himself.

Although Collins’ deployment into the WRP substantially overlapped with that of Scott, their reporting can usually be differentiated.

Collins joined the SDS in the second half of 1973 and began to report on the WRP in November that year.

Collins told the Inquiry he used a name that his managers gave him; it is not known whether that identity was that of a deceased child.

HN303 joined the SDS in the second half of 1973 and the first report on the WRP that the Inquiry identified to have been his is dated January 1974. Oddly this was for a meeting held in November 1973.

Collins’ target was the Trotskyist Workers Revolutionary Party , which appears to have remained his primary focus for his time in the field. However, during his deployment, the WRP asked him to spy on the fascist National Front and on a tiny faction within it. Notably, this was the only far-right organisation monitored by the SDS during its first 14 years of operation.

Workers Revolutionary Party

Targeting its north London branch, Collins’ reports on WRP meetings discussed policy and membership issues, newspaper distribution and demonstrations.

The first meeting that Collins reported on took place on 27 November 1973. It covered a rally held by the party in Trafalgar Square that day, with the WRP claiming it as a success. His report also mentioned how the organisation’s newspaper, Workers Press, would be distributed across north and east London.

One report, made on 7 May 1974, is typical of Collins’ reporting; it discusses an industrial dispute at the Ford car factory in Cowley near Oxford. This car plant was often a site of industrial strife.

Collins’ report of the WRP conference on 13 and 14 July 1974 is notable for its length – 23 pages – and its detailed, relatively nuanced account of the policies and personalities involved. It gave details about the WRP’s leader Gerry Healy and those who sought to challenge him. It also re-stated the party’s revolutionary aspirations. Collins is named in the report as one of the attendees, complete with his own Special Branch registry-file number.

The WRP instigated tight security measures for the conference. This indicates that Collins had gained enough credibility within the party to pass these security checks and attend the conference.

Further evidence of the trust Collins falsely instilled in party members comes less than 12 months after he started spying upon the WRP. In December 1974 he was elected chair of the Stoke Newington branch. It was this position that likely allowed him access the organisation’s central committee.

Reporting on the central committee

In his written statement, Roy Battersby said the central committee (CC) was democratically organised, and that its members represented branches across England, Scotland and Wales. There were between 20 and 50 people on the CC at any time.

Battersby said that the CC’s role was to settle the general direction of the party – the WRP’s ‘policy, structure, constitution’ – but recalled that the party also contained less formal, more powerful groupings that heavily influenced the direction of policy.

Nevertheless, Collins’ presence on the CC meant that he contributed to WRP decision-making. One example is that a CC meeting on 25 January 1975 discussed reversing previous policy to allow former WRP members to join without an interview. It is fair to assume that Collins voted either to support or reject the motion.

Collins also reported on WRP membership numbers, ranging between 2,500-4,000 people, and on the circulation of its newspaper, Workers Press. He noted that the WRP seemed relatively well-off and that the newspaper had an annual turnover of £156,000.

As discussed below, Collins’ reporting tails off from early 1976, with just two or possibly three reports over that year. The last report on the WRP released by the UCPI was dated December 1976 and concerned the suspension of a committee member for being indiscreet about matters previously discussed regarding personal relationships at the committee.

This appeared to be the end of the SDS’ interest in the WRP. However, this is disputed by some. What is not disputed is that no information in Collins’ reports on the WRP related to public-order concerns – supposedly the SDS operations’ main objective .

This lack of public-order threat apparently led SDS management to halt infiltrations of the WRP in 1977.

One of the SDS managers at the time, HN34 Geoff Craft, said in his evidence that he felt at the time that the WRP was not a public-order threat. It was rare for the SDS to decide that coverage of a group, once established, had become unnecessary.

National Front and the Legion of St George

At the behest of the WRP, Collins was asked to attend National Front meetings in the East End of London.

During the mid-1970s, the National Front (NF) staged provocative demonstrations through areas that had concentrations of migrants. Its members also attacked left-wing activists.

The Inquiry did not hear who from the WRP asked Collins to infiltrate the NF, why the group chose him, or how he went about his task. The first report on the National Front that the Inquiry attributed to Collins is dated 14 March 1975.

The report concerns the NF announcing a demonstration outside Islington Town Hall, a plan that both the group and its opponents would have publicised. It is equally plausible that this information came from an SDS source in a group opposing the NF. Indeed, the report stated that left-wing groups were aware of the plan.

The first report on the NF unambiguously attributed to Collins is dated 1 July 1975. It concerns a nine-person meeting addressed by a speaker from the NF’s headquarters in Croydon. Although Collins noted that nine people attended the meeting, he could name very few of them. This suggests that this NF meeting may have been Collins’ first.

His next report on this group of far-right activists was in December 1975, months later. This report identifies several individuals, suggesting that Collins was now more familiar with the group.

As Collins continued to target the NF in this period he is likely to have submitted other reports. These either no longer exist or have not been published by the UCPI.

The December 1975 report states that the people at the meeting were displeased with the NF leadership and were forming their own faction, which the report named the Legion of St George (LSG).

The report described how the LSG aimed to replace the National Front leadership. There is just one other report attributed to Collins, from January 1976, which states that NF members had defected to the breakaway National Party.

Despite this apparent, accidental, targeting the 1975 Annual Report listed the National Front and the League of St George as main targets for the SDS. The annual report described this part of Collins’ mission with some enthusiasm:

For the first time, an officer has penetrated the National Front at the instigation of a leading member of the Workers Revolutionary Party with whom he is particularly friendly and is thus obliged to lead a 'treble' life. By attending National Front meetings in the East End of London, he has discovered a small group of hard-line fascists, dissatisfied with the National Front leadership, calling themselves the Legion of St George, whose intent is to move even further to the right. Although few in number, such a group could well pose future public order problems.

However, the SDS’ enthusiasm was short-lived. A year later, the 1976 SDS Annual Report stated that Collins had been withdrawn as the information he obtained from infiltrating the National Front added little value to that available from other Special Branch sources.

It is not clear whether the reason proffered in the annual report is the real reason Collins was withdrawn from this fascist grouping. However, even if it is true, the fact remains that it was not the SDS but the WRP that – unwittingly – sent an undercover police officer to infiltrate the NF.

From the beginning of 1976 to the end of 1977, only a handful of reports could have come from Collins. A personnel review conducted by his SDS manager, Detective Inspector HN244 Angus McIntosh , on 10 January 1977 perhaps explains this and the real reason for Collins’ withdrawal from the fascist milieu. McIntosh noted a downturn in Collins’ productivity caused by:

a loss of morale, caused by a combination of unavoidable changes in operational conditions and the illness of a family member which dampened his normal enthusiasm for work.

The Inquiry’s interpretation was that Collins found his deployment into the far right ‘uncongenial’. It might be the case that the officer found infiltrating two groups at opposite ends of the political spectrum too much – and that this outweighed any net benefit of continuing the deployment.

As stated, although the WRP posed no threat to public order, like many other groups it was still spied on by the SDS. However, as part of Special Branch, the SDS also had a duty to provide MI5 with information relating to subversion and subversives.

It has been contested whether this became the SDS’ primary duty or was merely a convenient justification in retrospect.

Trade Unions

Officially, it was outside both the SDS and MI5’s remit to monitor lawful trade union activity. However, the SDS generally reported on all and any information it came across, so the official prohibition on surveilling trade union business was therefore unlikely to deter it.

In addition, official exceptions to this prohibition meant that reporting on trade unions became commonplace. These applied when ‘subversive’ organisations – as the WRP was labelled – became involved, or were suspected of being involved in, trade union activity.

One type of so-called subversive activity was ‘entryism’. This was the attempt by smaller left-wing organisations to gain influence in the British Labour Party or trade unions and was an issue within MI5’s remit. The subject is mentioned in Collins’ reporting.

In response to a query from MI5 regarding the term ‘sleeping members’, apparently used by the WRP, Collins filed a Special Branch report explaining that this was a tactic in which WRP members, when outnumbered on the shop floor by other groups such as the Communist Party of Great Britain, would not reveal their WRP membership.

This, Collins claimed, had allowed WRP members to progress to elected trade union positions. However, Collins also reported in the same document that the practice was uncommon.

Another report that concerned ‘entryism’ is dated 14 May 1975. It provides information that the WRP was considering infiltrating the Labour Party Young Socialists with a view to the eventual subversion of all its branches, something the WRP claimed to have achieved in Kent.

A report dated 1 August 1975 regarding the WRP delegates’ conference notes that Gery Healy called for winning over constituency members of the Labour Party to the WRP to create factions within the party.

Another example of reporting on trade union-related matters, outside of entryism, concerned a Shrewsbury Two Action Committee meeting. This was organised by the WRP at the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool on 29 July 1975 and attended by 800 people, including coach loads of individuals from London.

It is unclear whether Collins wrote this report, but HN298 ‘Michael Scott’ denied both authorship and having attended the meeting. There were also reports on the All Trade Union Alliance (ATUA), a group attended by trade unionists affiliated with the WRP.

MI5’s requests for information on the WRP show that the agency considered the group a potential subversive threat. However, this is not to say that MI5 controlled or directed the surveillance against the WRP – and whether it could be described as ‘subversive’ has also been questioned.

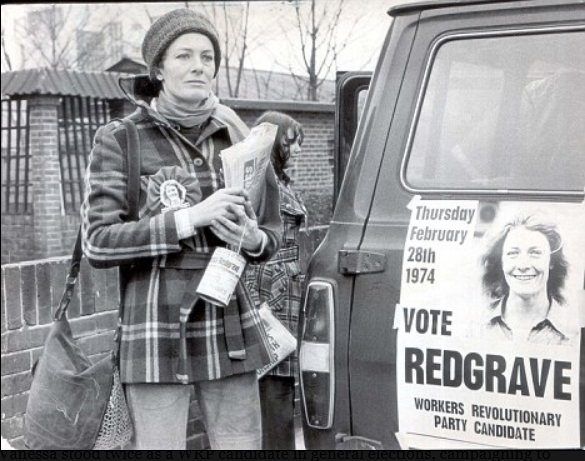

Liz Leicester and Roy Battersby pointed out that while the WRP engaged in political organising with revolutionary ends, it was careful never to stray into illegality, whether subversive or otherwise. Leicester added that the WRP participated in parliamentary democracy, standing candidates in general elections.

In his interim report, Inquiry Chair John Mitting stated:

Whatever its long-term aims, it was a small group which posed no threat to the safety or welfare of the state and was not therefore subversive.

A memo in September 1977 stated that Collins and HN13 ‘Desmond Loader’ were chosen as SDS representatives to discuss police handling of serious public disorder events.

At the top of the list was 'The Battle of Lewisham' and the lengthy Grunwick industrial dispute featured to a lesser extent.

This suggests that Collins and Loader were undercover at the event. However, the Inquiry could not locate any reports confirming that they were in Lewisham on that day.

The memo noted that Deputy Assistant Commissioner David Helm listened ‘attentively’ to the SDS officers at the meeting. It did not record the opinions they shared. Nevertheless, there is a four-page Special Branch report containing feedback from SDS officers on events at Lewisham, specifically the failings of the tactics employed by the police.

The report contained reflections and recommendations, including the drastic suggestion that police should have used CS gas and water cannons.

Attending that meeting with Helm was one of HN303’s final acts as an SDS officer. A Special Branch document recorded that by 18 October 1977, Collins’ withdrawal from his deployment was imminent.

The Inquiry on 30 July 2018 granted Collins real-name anonymity.

However, HN303 was unable to give evidence to the Inquiry due to ill health and has since died. Disclosure relating to his deployment was published on 4 May 2021, as part of Tranche One, Phase Two.