Roy Creamer was born in 1930 and served as a Metropolitan Police officer between 1954 and 1980. He was a founding member of the Special Demonstration Squad between 1968 and 1969 but had a back-office role and never went undercover.

Later, Creamer was involved in two police investigations into alleged anarchist bombing conspiracies: the Angry Brigade investigation in 1971-1972 and, in 1977, towards the end of his career, the Persons Unknown case. He retired from the Metropolitan Police in 1980, after which he worked for the Ministry of Defence.

On 16 May 2022, Creamer gave evidence to the Undercover Policing Inquiry that was broadly critical of the SDS and the tactic of undercover policing, repeating the opinion he had expressed in his written statement that the SDS ought to have been disbanded after the October 1968 anti-Vietnam war demonstration.

Although Creamer was happy to paint himself as the unit's foremost expert on the groups the SDS infiltrated, he sought to distance himself from the undercover deployments themselves. At the same time, he suggested he was indispensable to the unit’s work – and especially to its senior officer HN325 Conrad Dixon. He downplayed the threat posed by the October 1968 anti-Vietnam war demonstration.

Creamer submitted a written witness statement to the Inquiry in November 2020 and gave live witness testimony in May 2022. All quotes below are taken from his written statement unless stated otherwise.

Creamer was later asked for a supplementary statement on SDS’ input into public order policing.

Creamer joined the Metropolitan Police in October 1954 and, after training, was posted to a police station in Chelsea. After three to four years, including two years in a junior position at the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) , he moved to Special Branch in 1958.

Initially, he was posted to C Squad and dealt with left-wing matters. Creamer had a typical career path in Special Branch, including a spell on port duties in 1962-1963, before returning to C Squad in 1966.

He first had a run-in with anarchist Stuart Christie early in his Special Branch career; more were to follow. Christie had been arrested in Spain with explosives linked with a plan to assassinate Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco. It seems that, based on this, Special Branch was concerned that Christie would possibly be interested in harming French leader General Charles de Gaulle:

[On] at least one occasion, I was officially sent to visit activists to inform them about an upcoming state visit and to invite them not to do anything to disrupt it. The occasion I remember in particular was being sent to see Stuart Christie before De Gaulle visited [in 1960]. I gave him my name, showed him my warrant card and informed him I was in the Branch.

Creamer described some of the work he did on C Squad, distinguishing this form of traditional Special Branch activity from that of the undercover officers:

When I was on C Squad I was generally given the anarchists, so I found out information the old-fashioned way, simply by walking up and asking people. I was always open about my seeking information; I would attend meetings anonymously and not say I was a police officer.

Roy Creamer also harshly criticised Special Branch's monitoring of left-wing meetings, suggesting it was 'haphazard'.

Although an original member of the SDS when it was set up in July 1968, Creamer claims he was not involved in discussions about its creation before this. He was, however, aware that a variety of senior Special Branch officers proposed that they should have an 'undercover business'.

Creamer says that once this was agreed upon, the SDS was given 'carte blanche' to do the work. As he remembers it, there were only a few guidelines as the SDS started:

There were two or three rules: first, that the officers must not be agent provocateurs, be leaders or suggest anything or persuade others to act in a certain way; second, that they would be allowed to work without coming into the Yard, so they could always be scruffy and look like people of no consequences [sic].

Creamer's rank as a detective sergeant was a junior one. However, all SDS officers who were not deployed undercover seem to have taken on roles that could be described as managerial.

Roles in the SDS

Although of junior rank, Creamer suggests he was essential to the SDS in terms of providing the political background and other analysis on the groups that the SDS were spying upon, and in his influence on HN325 Conrad Dixon. However, Creamer makes it equally clear what he was not responsible for; the spying or the tasking or directing of undercover officers.

This might seem self-serving as, by doing so, he maintains his reputation as Scotland Yard's supposed expert on such matters while attempting to distance himself from the controversial aspect of the unit – the actual deployment of undercovers.

What Creamer did, however, is of significant interest. He explained that, alongside HN3095 Bill Furner , he undertook research and collated intelligence that came into the office via the undercover officers. He also mentored some of the new undercover officers and advised them where to look for the most interesting people to spy on.

Mentoring and advising

At the UCPI hearings, Creamer presented his role as advising on anarchist groups, 'I was the expert on these groups, and no one else was', and mentoring undercover officers. In his written statement, HN326 'Doug Edwards' recalls seeking guidance from Creamer and this accords with Creamer’s memory: 'I would discuss with HN326 about anarchist groups [that were] most likely to make trouble. [Some] were probably too intellectual and would not welcome people who did not know anything, and others were just drinking clubs.'

Another undercover, HN333 , also remembered Creamer’s advice and mentoring, saying. ‘In the era and the circumstances, I could not have asked for more oversight’. Creamer added that he offered ‘fatherly advice’ to other SDS undercovers not to get involved in taking drugs.

While he claimed he was advising on group dynamics – which ones had fallen out with each other – Creamer emphasised he had nothing to do with the choice of groups infiltrated. Still, it seems implausibly naive for him not to have assumed that was how his knowledge was being used. He also claimed to know which were the groups where 'the retribution might be worse if they found out about the deployment'.

Later, in 1978, HN304 ‘Graham Coates’ , an undercover who targeted anarchist groups, also sought advice from Creamer. Creamer gave the Inquiry his opinion about more senior officers with whom he interacted.

Opinions on senior officers

One telling anecdote that Creamer related during his testimony was of an interaction with Special Branch chief HN151 Ferguson Smith. Creamer said that having fought during the war and flown secret missions over Germany as an RAF navigator, Smith had a wartime attitude about security and ‘dangerous talk’. Creamer expressed his worry to Smith about what would happen if the existence of the SDS did get out:

I said, ‘Do you know, we ought to take the view that we'll do nothing that, when it comes – if it ever comes to light, that the public would not approve of’, and he Ferguson Smith said to me, ‘It will not come out’.

Creamer reflected on this in his oral testimony:

[...] of course, if you're going to start with that belief, that it will not come out, you're given carte blanche to do […] whatever you like, and I thought that was not right, but I couldn't really say it. I couldn't argue with him. He was the boss.

Despite this, Creamer said at the time he agreed that it should not come out, suggesting – with the gift of hindsight – that such knowledge could be a cause célėbre’ for the left.

Creamer also discussed SDS managers HN1251 Phil Saunders and HN325 Conrad Dixon. Although HN1251 was ‘nominally second in command of the SDS’ during his time, Creamer said he had little or no interaction with him; ‘I think he might have been more interested in accommodation [the cover flats] than me’.

He added – an opinion some might think surprising for an officer working within Special Branch – that Saunders was not interested in the political groups that the officers under his command were surveilling. Creamer made similar comments about Conrad Dixon, positing himself as the only one with an interest in the political groups the SDS were spying on.

Creamer portrayed the SDS' first boss, Conrad Dixon, as ambitious and eccentric; an 'adventurist'. While Dixon seems to have played an enthusiastic part in setting up the SDS, Creamer suggests he did not have an interest in political policing – and relied on Creamer for briefings.

Although Creamer sought to downplay his influence on how the SDS operated in some ways, the details he gave on his close working relationship with Dixon suggest otherwise. Indeed, Creamer described his role as that of the TV character Radar from the 1970s TV show M*A*S*H* who had a preternatural knowledge of what his commanding officer would ask of him next.

Despite Dixon’s purported lack of interest in political policing, Creamer was more positive about his management style, describing it as supportive and leading by example by attending meetings of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC) , while running the SDS with a loose rein. Reflecting on their close working relationship, Creamer said he, in effect, ghostwrote reports for Dixon:

If there was anything of major importance coming from the field officers, Conrad Dixon and I would discuss the information and I would then draft what I thought we should say in the report. I would put into words what I knew he ought to be saying.

Creamer said Conrad was primarily concerned with the welfare of the squad, leaving the political side to him. Creamer also suggested that he acted as a moderator in terms of the contents of the reports, saying: '[…] Conrad was concerned with trying to prove that all this business of undercover work could be done and it was an adventure. I was more concerned that, whatever else, we should not make a song and dance and make anybody be more alarmed than they need be.'

Here, Creamer subtly implies that Dixon would have been more likely to exaggerate the threat posed by activists for reasons of ambition. Whether this was the case is impossible to say. In these and other comments, Creamer is trying, unconvincingly, to distance himself from being part of the British surveillance state that he served for 40 years.

When talking about the SDS reports generated to supplement information that A8, the public order unit, had on planned demonstrations, Creamer gives a totally different picture of his and Dixon's relationship: 'Conrad would have the last say. I only had two pages to include a lot of information – how many people, the mood they were in, what was planned – and the report was for A8, for them to decide how many officers to bring to the event and what to do.'

He then goes on to say that a lot of information in these reports would come from Dixon and his undercovers – and, implicitly, as a consequence, less so from him as an expert:

When I did a report with Conrad, I would sign it and submit it, and he would then sign it and submit it higher up. It would be the report of the unit. Conrad was the source of a lot of my information for these summary reports. I only included a re-write of what [undercover] officers had said if it came from Conrad.

Creamer’s SDS reports and analytical style

Creamer wrote his first SDS report in mid-September 1968, dealing with the Anti-Imperialist Solidarity Movement:

In political outlook [privacy] is a communist but his views do not accord with either the orthodox Communist Party or the Maoists, and he is persona non grata with both groups. [Privacy] is a political adventurist, formerly a communist, for a long period Committee of 100 activist. And recently member of Notting VSC. The Anti-Imperialist Solidarity Movement cannot be expected to have much influence on the VSC controlling bodies, but as will be seen from the attached leaflet, its potential for mischief is very high.

In his written statement, Creamer said that he always assessed things. Indeed, this type of analysis – without judgment on its justification, usefulness, or accuracy – is notably missing from the vast majority of Special Branch reports disclosed by the Inquiry.

Efficacy of SDS during the 1968 demonstration

Creamer suggested that the most critical role the SDS played during the initial deployments around the October 1968 demonstration was a negative one, in that they found out there was no mastermind attempting to use the demonstration to bring about a revolution:

[W]hen we came to look at the VSC demonstrations, I knew full well we’d never find such a man. There wasn’t one. There wasn’t a group even that would do that. I think it was a situation that got out of hand, […]and that’s the worst you could say of them.

Creamer thought that the SDS provided useful information on various groups' intentions beforehand but, on the day of the demonstration itself, offered no valuable public-order intelligence. After the 27 October demonstration, Creamer thought the SDS would ‘pack up’ as the supposed dangers had passed and ‘the battle had been won’. He continued to work within the SDS until July 1969, however, leaving on promotion to detective sergeant.

Lack of Special Branch interest in fascists

Creamer, like Special Branch as an institution, played down the significance of the far right. Several SDS officers gave evidence to that effect during the Inquiry hearings. Referring to the period just before 1968, Roy Creamer comments:

In the early days, we were always sent to a far-right meeting as part of our kind of introduction into the Branch’s work, and it had been so discredited by what had happened during the war and that fascis[m] was absolutely, you know, [a] dead political idea all together. Nobody would take it up because they were wasting their time trying to persuade the public towards their point of view.

Creamer's views chime with those of other Special Branch officers who gave views about the far-right threat in the 1970s; that they believed the main public-order threat regarding the far right only materialised when left-wing activists attacked them:

'[T]he support for him, Oswald Mosley, from round and about was negligible, and to my mind … there was nothing interesting in them … they could be the victims of attacks by the left. That was the big problem. But on their own, they were of no account…'

Historians of the British far right disagree with Creamer's and Special Branch's assessment of British fascism as an idea whose time had passed by the 1960s. In 1962, Colin Jordan founded the National Socialist Movement (NSM), renamed the British Movement in 1968 with John Tyndall as its leader.

A meeting of NSM supporters in Trafalgar Square on 2 July 1962 was disrupted by ‘Jews and Communists', in Jordan's words, leading to a riot. This did not kill off the fascist resurgence, however, as historian Richard Thurlow explains:

The formation of the National Front in 1967 was the most significant event in the radical right and fascist fringe of British politics since [World War Two]. It represented the culmination of a process whereby various strains of revisionist strands of neo-fascist and racial populist politics came together in an attempt to form a mass party…

The racist attacks and violent demonstrations of the National Front in the 1970s and 1980s would suggest that Thurlow’s analysis has some weight.

In his post-SDS career, Creamer became involved in police investigations into alleged anarchist bombing conspiracies. One was the Angry Brigade investigation of 1971-1972.

The Angry Brigade

On 12 January 1971, a bomb exploded in home secretary Robert Carr's house. Although the investigation was headed by CID detective Roy Habershon, a small group of Special Branch officers, including Creamer, were also attached to the investigation due to the suspected involvement of anarchists in the attacks; see also Conrad Dixon's profile for claims about his involvement in the investigation.

It is also notable that although the SDS' involvement in and intelligence on the Angry Brigade was nearly non-existent, it is mentioned in four SDS Annual Reports. These mentions are used to justify the SDS' existence, even though it did not provide any information on them.

HN349 may have been tasked with infiltrating anarchist groups associated with the Angry Brigade. After nine months, however, his deployment was aborted at his own request as he judged his mission unsuccessful.

The Inquiry published one report by Creamer on the Angry Brigade, dated 5 March 1971 and submitted by Conrad Dixon, though by that time both had left the SDS. Written relatively early in the investigation, it is a review of what was known so far and the arrests made; it also includes some analysis.

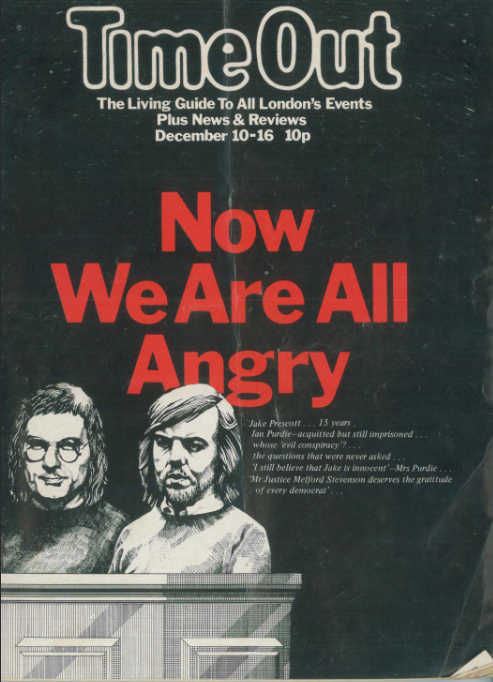

One example of this was the assessment that most Angry Brigade members came from 'middle-class backgrounds' and were involved in the women's liberation struggle, alongside mentions of the North London Claimants Union as a 'somewhat anarchist enterprise'. During the investigation, Roy Creamer was involved in a police raid of then-radical magazine Time Out.

Creamer reports 1974-1977

Creamer was back in C Squad by 1974 and had reached the rank of detective inspector. The next set of reports related to Creamer begins in October 1974 and ends in September 1977. He signs some; others are marked up for him to assess. He comments that at the time:

I was in charge of the desk for left-wing groups such as the anarchists, communists, Maoists and fringe groups. It would have been up to the bosses to decide what information was sent for me to see. [… ]

The first of his reports from this period relates to a meeting of the Communist Federation of Britain (M-L). The next four relate to the deployment of undercover SDS officer HN297 Richard Clark, 'Rick Gibson', into the Troops Out Movement (TOM) and were all sent to Creamer.

During his Inquiry hearing, Creamer was confronted with the fact that Rick Gibson had placed himself in a decision-making position within TOM and was involved in group dynamics and conflict. Creamer said that although he would have been aware these were SDS reports, he did not know that ‘Rick Gibson’ was an undercover officer. David Barr, Counsel for the Inquiry (CTI), asked him:

'[…] Would you have been concerned if you had known that the person who was calling himself “Rick Gibson” was an undercover police officer that he was also assuming high office?'

Creamer answers:

[Y]es, in the Troops Out Movement or whatever. It shouldn’t have happened. Back then, let’s face it, sir, I couldn’t […] interfere with what the SDS were doing. I mean, apart from anything else, Troops Out Movement is related to Irish matters, isn’t it?

Creamer's claim that he had no responsibility for these reports is less than convincing. Groups like TOM were under C Squad's purview , even if groups that campaigned on the conflict in Northern Ireland were not his speciality. Perhaps more convincing is his admission that even if he had known about the activities of 'Rick Gibson,' he would not have challenged them.

A report for 15 July 1977 relating to a different undercover officer, HN354 Vince Harvey, ‘Vince Miller’ , who had a sexual relationship with an activist he was spying on, is signed by Creamer. When asked at the Inquiry, Creamer claimed he knew nothing about the sexual relationship. How plausible his and other former SDS officers' blanket denials about such matters are, is set out in the chapter on undercover officers having sexual relationships.

Creamer signed seven more reports in July 1977, see table. At this time, Creamer suggests that he must have been covering for a more senior officer from C Squad, as officers of his rank would not normally sign off on reports. As an officer with C Squad, Creamer did not rate the SDS highly for helping to plan for policing demonstrations, as the unit was:

[...] kind of snooty about it. They would only say, for example, ‘Oh, we haven’t got anybody interested in that. … if it’s not I[nternational] S[ocialists] and if it’s not … I[nternational] M[arxist] G[roup] or one the groups they were involved in, they couldn’t tell you any more than anybody else.

The Persons Unknown investigation

HN304 ‘Graham Coates’ was an SDS undercover deployed into anarchist groups between 1976 and 1981. He recalled that he was sent on a ‘trial run’ by Roy Creamer to a college in north London to see if he could find out some information about some political organising there. He presumably passed the trial as Coates was subsequently recruited to the SDS.

The ‘Persons Unknown’ police investigation in 1977 and eventual trial in 1980 concerned six anarchists involved in a ‘conspiracy to cause explosions’, though the original criminal charge was replaced with ‘conspiracy to rob and possession of explosive substances’. Anarchist Stuart Christie recalled in his memoirs that Roy Creamer coordinated the investigation.

During Coates' infiltration of anarchist groups, Creamer signed off two of his reports in September 1977. The latter was based on Coates' infiltration of a commune at 29 Grosvenor Avenue in north London, which housed some of those involved in a legal defence group for the Persons Unknown defendants. Creamer was not questioned on either of these reports by the Inquiry.

The 1978 SDS Annual Report boasts that two of the people put on trial were identified by the SDS. All were found not guilty. It seems strange that Creamer, who allegedly oversaw this investigation, did not mention the SDS’s part in it at the Inquiry hearings.

Casting further doubt on the integrity of the information contained in this SDS Annual Report, Coates, does not mention the SDS’ identification of the suspects either. This is strange, given he was reporting on groups connected with the defendants both before and after their arrests. Coates also said he never had contact with people who participated in such 'serious offences', suggesting his contact was limited to the legal support group and not with the defendants themselves.

The last time Creamer appeared in documents released by the Inquiry was in a 16 March 1978 report of a meeting with MI5, which he attended with then head of the SDS, HN318 superintendent Ray Wilson.

This was towards the end of Creamer's posting with C Squad. Given Creamer’s reputation as Scotland Yard’s expert on anarchism, it perhaps is no surprise that the meeting focused on an MI5-hosted conference about the UK-based anarchist movement.

In the meeting, officers from MI5 agreed not to use any material from Special Branch without prior clearance and that they would provide two lists of groups and individuals they held information on for cross-referencing One list was of UK groups linked with international ones; the other was of individuals connected with the Angry Brigade, which seems odd given that this group had not been active since 1972.

The Note to File includes a request from MI5 that the SDS put someone into a group called Revolutionary Struggle, which had its main presence in Dublin. It is not clear that Creamer remembered or even knew that Revolutionary Struggle was mainly based outside the UK. More generally, Creamer went on to say that the relationship between MI5 and Special Branch was one of 'master and servant':

Anything from the Security Service was treated with great, you know, sort of alacrity. If they wanted it, they were the people that mattered, because they were – I’m not saying they were our supervisors, but they were on a level higher than us and, you know, we should do what they want really.

After leaving C Squad in 1978, Creamer moved to the Naturalisation Squad for the last couple of years of his service: ‘This was like a rest,’ he commented. Creamer retired from the Metropolitan Police in 1980, moving on to work for the Ministry of Defence. Given Creamer’s background, this would have likely been for the military police, given that he said former SDS colleague HN3095 Bill Furner was his boss.

No application for anonymity was made on Creamer’s behalf. He submitted written statements on 16 May and 20 September 2022 and appeared before the Inquiry on 16 May 2022.