Conrad Hepworth Dixon was born on 27 January 1927 in Gillingham, Kent. After he attended a fee-paying school in Salisbury, Dixon’s Metropolitan Police record states that he started a degree but interrupted his studies to join the army in 1945, aged 18.

After this he joined the Metropolitan Police in 1947 before transferring to Special Branch in 1950. Rising through the ranks, he was involved in personal protection before moving to B Squad which dealt with many of the same political groupings that the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) would.

According to his own account, Dixon claimed it was his idea to form an undercover squad to deal with the forthcoming 27 October 1968 anti-Vietnam war demonstration. More certainly, he led the squad from its formation in July 1968 to early 1969.

Dixon oversaw personnel management but also attended activist meetings. It was he who proposed that the SDS should continue, which was accepted by senior Metropolitan Police management in November 1968. Dixon was reassigned later in 1969 to a Special Branch unit in Wales, focusing on Welsh-nationalist activists.

Returning to London in 1970, he joined a team investigating the Angry Brigade who participated in a bombing campaign in London at the time. Dixon retired from the police in 1973. He died in 1999, having written his own obituary detailing his police career, including the SDS, for publication in The Times.

Some of the assertions Dixon made about his police career in the obituary are contested and seemed to be designed to ensure the legacy he wanted, although his association with the SDS was later to be seen in a less than flattering light.

Conrad Hepworth Dixon was born on 27 January 1927 in Gillingham, Kent and was educated at the Bishop Wordsworth's School in Salisbury. His record of service says he enrolled for a degree. He did not complete it, however, joining the Royal Marines as a commissioned officer in 1945 at 18, then taking another job before joining the police in 1947.

On demobilisation in 1946, he got a job with a football pools company, but according to his self-penned obituary, a 'bizarre sequence of events' led to him having to choose between becoming a coal miner or joining the Metropolitan Police. It was likely that Dixon was offered this choice under the Control of Engagement Order 1947.

Dixon described his choice of the Metropolitan Police as less than auspicious as it was thought of at the time as being both 'ill paid' and 'poorly regarded' – as work for the 'strong' and 'not-too-bright'.

He joined the Metropolitan Police as a police constable on 8 December 1947 and transferred to Special Branch on 29 May 1950. He was promoted to detective sergeant in 1959, became a 'first-class sergeant’ on 6 January 1961 and was subsequently promoted to detective inspector.

Personal Protection Squad

Not all Dixon’s roles in Special Branch are known. It is clear that he spent some time within the personal protection – bodyguarding – squad in the late 1950s and early 1960s. He claimed in his obituary that his duties included the security of Kenya's president, Jomo Kenyatta, and Pakistan's president, Ayub Khan.

Dixon added that he also provided protection for Sir Henry Brooke, who served as the Conservative British home secretary between 1962 and 1964, whom he 'came to admire and respect'. In February 1964, Dixon was promoted to the rank of detective inspector.

B Squad

Until 1969, B Squad was the part of Special Branch that monitored ‘Fascism, Anti-Fascism, Nuclear Disarmament, Trotskyism and Irish Extremists’. Dixon was part of B Squad from at least August 1966.

In the same year, Dixon attended the Intermediate Command Course at the Police College. While in B Squad, on 22 August 1967, Dixon attended a meeting with the agent-handling section (F4) of MI5 to discuss the use of informants.

Just prior to the formation of the SDS, a small number of reports relating to the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC) bear Dixon's name. The most significant of these is dated 2 April 1968.

It is a critical document in the history and formation of the SDS. The report analyses the 17 March 1968 anti-Vietnam war demonstration in central London, during which significant disorder broke out. The main body discusses the causes of the protest and identifies its leaders, including Ernie Tate and Tariq Ali, both core participants in the Inquiry.

While implying that violence by marchers may have been planned, even by foreign agents, the report’s main conclusion was that the Metropolitan Police lacked intelligence about the organisations involved and that this should be rectified in future.

Dixon claimed in his obituary that until the SDS was formed no 'intelligence was coming in' from organisations such as the VSC. Special Branch files published by the Inquiry show this to be untrue: for example, a large Special Branch file on the VSC refers to various sources of intelligence prior to the SDS’ formation on 31 July 1968, including from an informant.

Dixon was, according to his own account, the driving force behind the unit's creation. There is no doubt that Dixon was the most senior officer during the SDS' first year of operation - and created a plan for the unit's continuation beyond October 1968. He was also respected by many of his squad, though criticised by others - especially his back office seargent HN3093 Roy Creamer.

Foundation and Continuation of the SDS

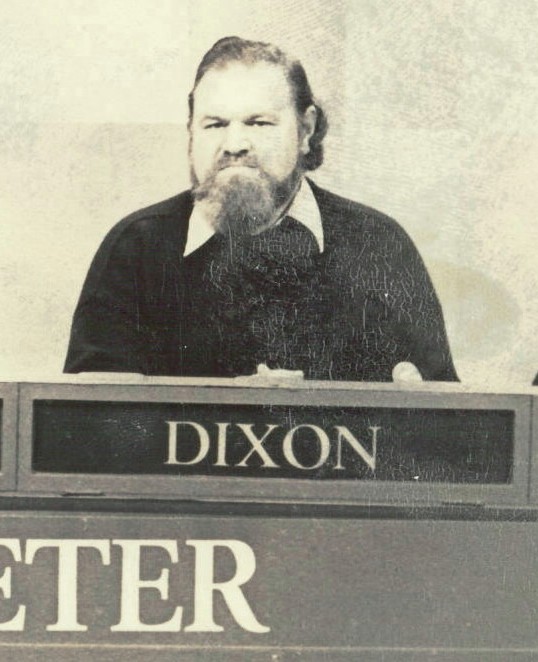

The SDS was formed on 31 July 1968, with Detective Chief Inspector Conrad Dixon as its most senior officer. Details of how and why the squad was created are dealt with at a dedicated page.

Dixon also later proposed that the SDS should continue, adhering to the plan he proposed in his 26 November 1968 paper, ‘Penetration of Extremist Groups’. This was both a resumé of what had happened to date and a future plan about how such an undercover police squad should operate. It is unclear what effect this document had on the operations of the SDS going forward, as there were significant departures from the blueprint. The decision making process to continue the SDS is also examined at the dedicated page mentioned above.

Roles and Personality

Dixon was the senior officer in the SDS and therefore had responsibility for communicating with more senior Special Branch officers, such as HN2857 Chief Superintendent Cunningham and Special Branch boss Commander HN151 Ferguson Smith.

Dixon was usually the most senior signatory to Special Branch reports authored or based on undercover officers' surveillance. Dixon also went to public meetings himself. Writing about events surrounding the 27 October 1968 anti-Vietnam war march in his obituary, Dixon claimed that he ‘led from the front, and when students occupied the London School of Economics, he was first up the steps and promptly took charge of the telephone exchange so as to control press releases.’

Detective Roy Creamer was a back-office sergeant in the SDS between 1968 and 1969. His evidence should be assessed with the caveat that while he seems to provide the most useful (and critical) commentary on Dixon and the early days of the SDS, it is notable that this evidence also shifts any blame from him to others.

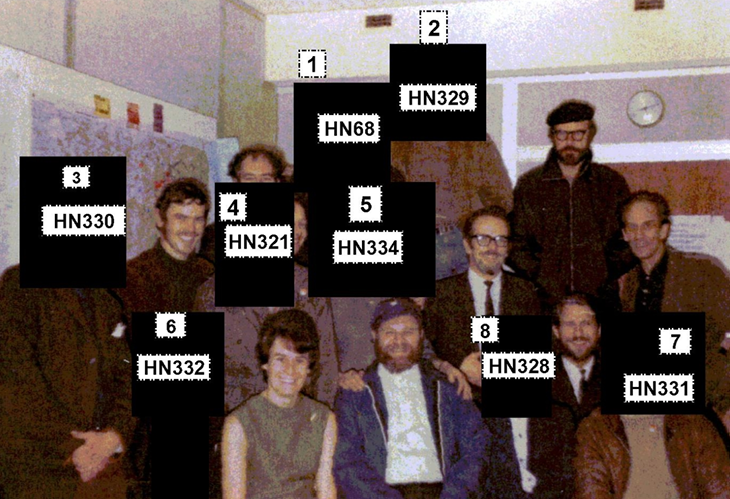

Creamer said that Dixon’s major preoccupation was with personnel issues within the Squad. This was a strength of Dixon's, at least according to some of those who worked with him. For instance, HN334 ‘Margaret White’ wrote in her witness statement that: ‘Conrad Dixon’s management of the SDS was not something I would question. He was very friendly and approachable.’

HN333 also suggested that Dixon ‘was not in it for personal glory’. HN328 Joan Hillier and HN218 ‘Barry Moss’ were also positive about Dixon as a manager.

Creamer was the officer who worked most closely with Dixon, describing himself as an indispensable right-hand man. He gave evidence that:

Conrad Dixon ran the SDS with a light reign [sic]. He wanted everyone to be comfortable and knew that they were taking risks. He was supportive. He led by example because he joined a group and did the same as the undercover officers.

However, some suggested that Dixon did not take his role or the SDS entirely seriously. For instance, Creamer said Dixon used the absurd cover name, Captain Birdseye and wore a sailor’s hat when he attended VSC meetings.

More damningly, Creamer also said that Dixon's drive to set up the SDS was based on personal ambition rather than any particular interest or expertise in political policing. Another colleague from 1968, Undercover officer HN336 ‘Dick Epps’ was blunter, suggesting that Dixon was in fact a 'brash chancer'.

In addition, Creamer is critical of Dixon's decision-making and knowledge of the groups that the SDS was targeting. He also suggests that he ghost-wrote Dixon’s reports:

If there was anything of major importance coming from the field officers, I would have been told. Conrad Dixon and I would discuss the information and I would then draft what I thought we should say in the report. I would put into words what I knew he ought to be saying.

Creamer again reflects that Dixon was not by any means an expert on the groups they were to surveil, saying instead he 'relied on my knowledge of the left a bit as it was not his speciality’. Also, devastatingly, Creamer said that one of his roles was to ‘restrain him from doing anything really stupid’.

In his obituary, Dixon's account of himself is somewhat different, portraying himself as an expert on the groups the SDS spied on, as well as being a man of action who also liked to be – and often was – at the centre of the action and would not be suited to a desk job.

From mid-1969, the number of SDS-related reports bearing Dixon’s name tailed off, and by November 1969, he was seconded to a unit concerned with Welsh nationalism. He also later attended a meeting with the Security Services as Chief Superintendent of C Squad (see below).

After leaving the SDS, Dixon worked in a special unit monitoring Welsh-nationalist groups, which were at the time seen as a serious threat by Special Branch.

He was then seconded to a criminal investigation into anarchist group The Angry Brigade, which had conducted a bombing campaign in London. Finally, he was appointed chief superintendent of C Squad.

Dixon and the Free Wales Army

Byddin Rhyddid Cymru, The Free Wales Army (FWA), was a paramilitary group founded in 1963 with the goal of creating an independent Welsh republic. Its formation was partly driven by perceived injustices from the British government, such as the flooding of the rural community of Capel Celyn in Gwynedd.

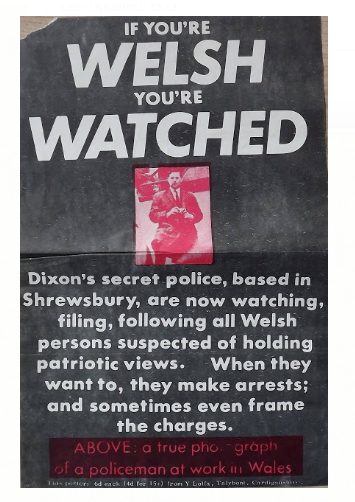

The FWA conducted marches in military attire and took responsibility for several bombings. Little is known about the extent of Dixon’s involvement in the investigation into the FWA. There was a dedicated police unit known as The Shrewsbury Unit that was explicitly set up to deal with Welsh-nationalist extremism. In his obituary, Dixon claims a prominent role, which led to the collapse of the Free Wales Army:

Dixon’s skills were next called upon in Wales, where the Free Wales Army was setting off minor explosions and was reported to be taking lessons from the IRA. The separatists were soon alarmed by the penetration of their groupuscules, and even produced a poster about the danger, which appeared on a host of telegraph poles. It showed a listening figure at a mountain crossroads, with the caption 'Dixon’s Secret Police in Wales.' Before long the principal bomb-maker and his assistant were arrested, and the movement collapsed.

The poster that Dixon refers to above still exists. There is also one Special Branch report, dated 11 November 1969, which discusses a Special Branch intelligence source who might have intelligence about the nationalist protests against the investiture of Prince Charles in 1969.

Beyond this, there is little evidence to confirm the extent of Dixon’s involvement in the investigation – not least the implication in his obituary that he was responsible for the movement’s collapse.

In 1970, Dixon signed an SDS report as chief superintendent. At this time, the SDS did not have a dedicated officer of that rank – and different chief superintendents signed off on the intelligent reports. This might suggest that Dixon had returned to London from his secondment to Wales, but in what role remains unclear.

Angry Brigade investigation

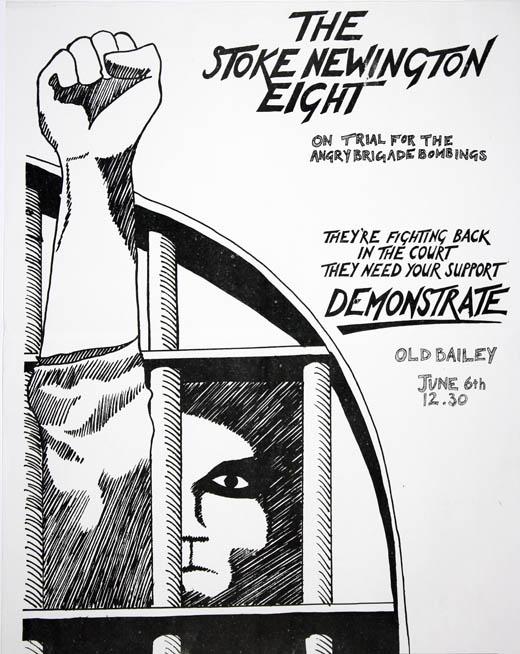

On 12 January 1971, a bomb exploded in Home Secretary Robert Carr's house. This, and a series of other explosions, was claimed by an organisation calling itself The Angry Brigade in a series of communiques.

Although the investigation was headed by CID detective Roy Habershon, a small group of Special Branch officers, including Roy Creamer and Dixon, were attached to the investigation due to the suspected involvement of anarchists in the attacks. According to Dixon’s obituary he played a crucial part in the investigation:

[Dixon] headed the intelligence unit for the Angry Brigade [inquiry]. Conrad Dixon found they had two weaknesses. They lived in communes which were natural ports of call for other revolutionaries and financed their activities by cheque and credit card fraud.

A 1975 book on the Angry Brigade by BBC journalist Gordon Carr, however, featured an interview with Roy Creamer, in which he stated that Habershon's work led to the arrest and eventual trial of several suspects. Specifically, Creamer gives Habershon credit for the cheque-fraud angle, which Dixon claimed for himself.

The Inquiry published one contemporaneous document regarding the investigation into the Angry Brigade. Composed by Creamer, it was authorised by Dixon, suggesting that he participated in the investigation, as the most senior Special Branch officer.

Chief superintendent C Squad

An MI5 document dated 16 January 1973 suggests that Dixon was chief superintendent of C Squad in 1972. The 'note to file' records details of a conversation with new Special Branch C Squad boss HN 1254 Rollo Watts , who mentioned that he had just taken over the role from Conrad Dixon.

Another document details liaison between Special Branch and MI5 earlier in 1972. Dixon's presence is noted, but although his rank as a chief superintendent is mentioned, his precise role is not.

Dixon retired at the rank of detective chief superintendent in 1973 after 25 years in the Metropolitan Police. In his draft obituary, Dixon gave the impression that he had been begged to stay, writing:

In 1973, there was strong pressure on him to conform – and go to Bramshill Police College for training as an embryo Chief Constable. He argued passionately that it made no sense to transform a leader of irregulars into a garrison commander sitting behind a desk but his superiors would not give way and he left the service to start a new life as a writer and academic.

However, according to his MPS service record, he was 'discharged 11 August 1973 at age 46 on the grounds of ill health’.

Three years later, it became known that Dixon had been less than discreet about the secret existence of the SDS. In 1976, an MI5 document referred to a training course that Dixon had run before retirement for police forces outside London, where he detailed SDS operations.

The note suggested that there was knowledge of the SDS throughout England's police forces. The dissemination of the information was said to have been a 'mistake' on Dixon's behalf.

Dixon wrote in his obituary that after retiring he completed a degree at Exeter University and a PhD at University College London and subsequently published several monographs on nautical navigation. He was also a director of the charity Westminster Boating between 1991 and 1997.

Dixon died on 13 April 1999 aged 72. He had prepared his own obituary, which was published by The Times on 28 April 1999. The Inquiry also disclosed a longer version, which had not previously been made public.

Alongside this is a 'file to note', which SDS senior officers HN53 and HN58 examined. Aside from a request to change the unit's nickname from the 'Hairy' to 'Scruffy' Squad, they expressed no concerns about the publication of the notice.

Dixon had died by the time the Inquiry had started and no application was made to restrict his real name, which was already in the public domain following the publication of his obituary. Inquiry Chair John Mitting issued a Minded To notice on 3 August 2017 that Dixon’s real name would be published. That the nominal HN325 referred to Dixon was only revealed when Inquiry hearings began in 2021.

See the documents tab for the full set of reportsl and procedual documents relating to Dixon.