HN354 Vincent James Harvey, cover name ‘Vince Miller’, was an undercover officer in the Special Demonstration Squad.

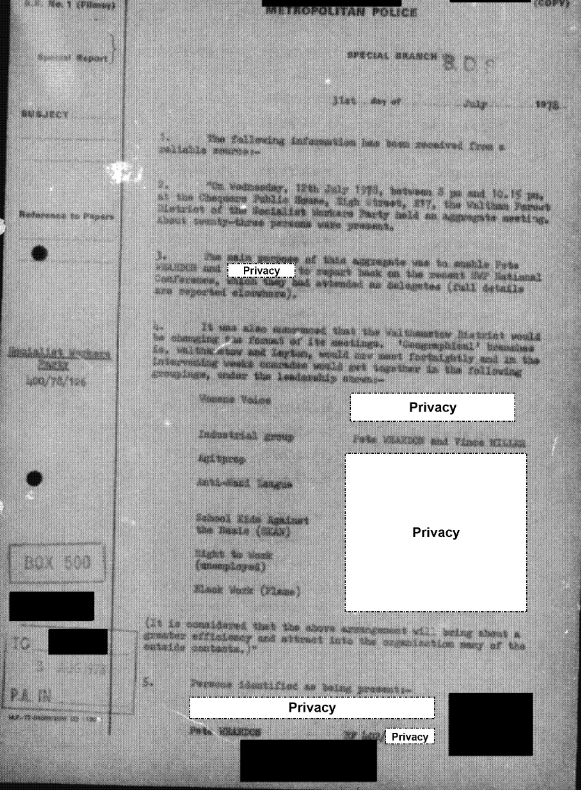

While deployed undercover by the SDS he infiltrated the Walthamstow branch of the Socialist Workers Party from 1976 to 1979. He had four sexual relationships during his deployment.

One of those relationships was with a Walthamstow SWP member who uses the pseudonym ‘Madeleine’. While Harvey characterised the relationship as a one-night stand, ‘Madeleine’ stated that their relationship lasted ‘up to two months’. She added that the dynamic between them had seemed ‘to hold out a lot of promise’ for a lasting relationship.

During his deployment, Harvey witnessed and reported on frequent anti-fascist activity by the SWP to counter the violent threat posed by the fascist National Front. This included, in August 1977, the ‘Battle of Lewisham’.

Harvey submitted a written statement on 18 November 2019, which he supplemented on 10 March 2021. Unless otherwise noted, the following information comes from the supplemented statement.

On receiving a written statement from ‘Madeleine’ in February 2021 detailing her relationship with Harvey, the Inquiry agreed to publish his real name, having previously decided it should be kept secret, the officer having gone on to a high-profile policing role.

On 10 and 11 May 2021, Harvey and ‘Madeleine’ gave live evidence during the Inquiry’s evidentiary hearings.

Harvey joined the Metropolitan Police on 31 August 1971 and was posted to West Hampstead police station from December 1971 until April 1974. On 5 May 1974, he joined Special Branch as a detective constable.

He was first assigned to B Squad until October 1974, when he moved to S Squad, where he stayed until May 1975. From there he moved to E Squad until December 1975, returning to B Squad until February 1976.

Harvey said his selection for the SDS was informal: ‘I bumped into SDS manager Detective Inspector HN34 Geoffrey Craft in the corridor. he pulled me aside and asked if I was interested in joining his team. I said that I was.’ Harvey joined the SDS on 2 February 1976.

Tradecraft and training

The SDS did not provide its undercover officers with formal training. Like other undercovers he picked up things while spending time in the SDS back office. There, while building his cover identity, he saw handwritten reports from undercovers already in the field, answered the phone and attended the twice-weekly safehouse meetings.

He was instructed by the SDS office ‘to go to the Births, Deaths and Marriages registry at St Catherine’s House in London’ to find a deceased child’s identity to use. Unlike other undercovers, Harvey did not spend a great deal of time developing his back story, saying he made up his ‘legend’ as he went along. For instance, he told members of the SWP that both of his parents were dead. Those spied upon said Harvey told them he grew up in a children’s home.

Harvey’s cover job was installing portable cabins and suspended ceilings. He said he made sure he had the appropriate tools in his van for the occupation and would occasionally visit the cover employer. He recalled that SWP members would call his cover employer if they needed to contact him, and that the employer would take a message.

A unique feature of Harvey’s tradecraft was how he always made sure to be ‘first to the bar’ when meeting activists in the pub. This was less driven by his enthusiasm for alcohol than it might have appeared, Harvey said, and was, in fact, tactical.

Although Harvey agreed that he drank more than the genuine SWP members he associated with, he claimed his main motivation for getting to the bar first was to position himself in the pub to check whether anyone there might know his true identity. Harvey added that even when out with his family, he would choose a seat to observe who was coming into the premises.

Harvey almost exclusively infiltrated the Walthamstow branch of the Socialist Workers Party between late 1976 and the autumn of 1979. However, he also attended meetings of the branch’s ‘parent’ Outer East London and Waltham Forest districts.

The officer said he was not explicitly tasked with infiltrating any specific group but understood that one of Special Branch’s primary functions was counter-subversion. In addition, he was asked to look at any group in a part of London that the SDS did not cover at the time.

In Harvey’s view, the Socialist Workers Party was subversive, and Walthamstow in east London was not covered by the SDS at the time. He added that the SDS only targeted ‘the far left’ and ‘anarchists’, narrowing his choices. Groups on the right of the political spectrum, he said, were not deemed ‘subversive’.

Harvey approached the group by buying the Socialist Worker newspaper in Walthamstow, where he had his cover accommodation. After doing this a few times, he was invited to the Rose and Crown pub in Walthamstow to join the branch members.

In 1977, he became a member of the SWP, paying a subscription. He became involved in the branch’s social life, attending parties and other social gatherings hosted by its members. Having stated that he was a heavy drinker, he admitted to having driven home drunk from social gatherings.

Harvey became treasurer of his branch on 12 April 1978, and went on to become treasurer and a member of the social committee of the Outer East London district in July 1977. He commented:

Becoming treasurer was fantastic for information and intelligence gathering. I was given a list of all the members, along with their addresses. I also had the task of knocking on the doors of members to check that the address was current and to chase subscription payments. This gave me an insight into occupations and living arrangements.

Grunwick and trade unions

In 1976, workers at the Grunwick film-processing factory in the London borough of Brent went on strike seeking union recognition, sparking a dispute that lasted into 1978. It was a pivotal moment in British labour history, partly because female Asian workers led the strike and partly because the strikers received substantial support from other trade unions – not least the National Union of Miners, led by Arthur Scargill.

Many left-wing groups supported the strike, including the Socialist Workers Party and there were days when the picket became a particular focus for trade unions and political groups.

Harvey filed a report on 31 May 1977 about a plan for a seven-day mass picket planned for June. He also recalled attending one of the many days of picketing at the factory in 1977. This may have been on 7 November 1977, when 8,000 protesters took to the streets of Brent, and were confronted by police as they attempted to stop ‘scab’ workers crossing the picket lines. Harvey commented:

I understand the picket was intended to prevent non-striking workers from attending work. I understood the picketers would prevent anything or anyone from leaving the factory by blocking the road with their bodies, having confrontations with police, and being violent on some days. I recall the uniformed police had ample numbers to get the coaches through.

More generally, Harvey maintained that Special Branch never tasked him to report on events that involved trade unions. Like many former Special Branch officers who gave evidence at the Inquiry, he said such reporting occurred only when subversive groups like the SWP became involved.

It is questionable whether police can make that distinction; many SWP members were also trade unionists and many trade union members also belonged to the many left-wing groups. Harvey also claimed not to recall being part of an SWP ‘industrial group’, despite a report dated 31 July 1978 that states otherwise.

Confrontations with the National Front

Alongside industrial disputes, the central preoccupation of the SWP – and the left in general during the mid to late 1970s – was the threat from the fascist National Front (NF). Harvey provided intelligence on the Battle of Lewisham, discussed below.

While confrontations between the SWP and NF were frequent, they were mostly on a smaller scale – with members of the two opposing organisations competing for pitches to sell their newspapers. East London had a long tradition of racial diversity and resistance to fascism, making it a target for the National Front. Harvey described how clashes broke out there on a weekly basis:

I can recall public disorder and violence at Brick Lane marketplace most Sundays. There was a territorial fight between the NF and the SWP. Both groups wanted to sell newspapers at the market. Often it would depend on who attended first. I recall spending the whole night there in order to obtain the best selling point.

Harvey also recalled that a general callout would be made if the National Front turned up in more significant numbers at newspaper pitches. He said:

There’s an awful lot of people who would support activities against the National Front who weren’t particularly left wing or Socialist Workers Party…they would definitely come out and assist you if it meant confronting the National Front

He described these incidents as ‘violent scuffles’ – with uniformed police normally intervening before they became more serious. That assertion differs from left-wing activists’ views at the time; many felt that the police favoured the far right. ‘Madeleine’ noted that the killers of Blair Peach, who belonged to the Metropolitan Police’s Special Patrol Group, owned Nazi regalia.

Harvey gave one detailed account of travelling in a car back from a SWP meeting, when one of the SWP activists spotted three National Front skinheads and leapt out to confront them. The officer said he intervened to ‘drag him away’ from a fight the activist would probably have lost.

Harvey also reported SWP members preparing to arm themselves with ball bearings and slingshots to defend themselves against the NF, but did not recall anyone using them. However, ‘Madeleine’ made it clear that, to the best of her knowledge, using weapons was never considered or discussed within SWP circles. Harvey spoke of other instances where he claimed violence occurred:

I recall […] a Jewish teacher, hurl[ed] himself into a group of skinheads. He had an absolute fear of the right wing because of the Nazi actions during the second World War, it was odd because most of the time he was a placid school teacher.

Former SWP activists including ‘Madeleine’, Julia Poynter and Lindsey German told the Inquiry that if activists from their party ever had to resort to force, it was to defend themselves or others.

One instance of the SWP defending people targeted by violent racists involved a couple, a Black woman and her Jewish boyfriend, whose home the National Front attacked. Harvey did not recall it during his hearing, but he reported at the time:

[a] rota of comrades who were to sleep at [an address in] Dagenham to protect a black girl resident there and her Jewish boyfriend from attacks from the NF.

In her written statement, ‘Madeleine’ emphasised that such incidents were common and that left-wing activists feared being attacked – they made sure they never went home from meetings alone. ‘Madeleine’ recalled National Front members attacking a woman who sold the SWP newspaper outside Barking tube station and breaking her pelvis. HN304 ‘Graham Coates’ also reports on left-wing meetings being targeted by the National Front.

Like other witnesses in the Inquiry, ‘Madeleine’ also questioned why the police seemed to be more concerned about groups opposing racist attacks rather than those committing them. Harvey stated that SWP members’ concerns were at the top of their agenda:

I think it’s important to express the depth of feeling against […] fascist groups that many members had. This wasn’t just random hooliganism, they really believed that the National Front had to be stopped, and that the prospect of them gaining any greater power would be dreadful for all.

Battle of Lewisham

The so-called Battle of Lewisham took place on 13 August 1977 when police, National Front supporters and anti-fascists clashed in London. The National Front had planned to march through the ethnically diverse boroughs of south-east London. Despite pleas from local people and politicians, the police and Home Office decided to let the march go ahead.

A coalition of political groups and local people opposed the march. The 500 National Front marchers were met by an estimated 4,000 opposing protesters. The police’s attempt to force the march through led to clashes within Lewisham town centre.

The event was notable for being the first time police turned out in riot gear on the UK mainland. The clashes at Lewisham ended with hundreds arrested or injured.

Several resources recount the day in detail. There is also a substantial amount of documentation published by the Inquiry. Only Vincent Harvey’s reporting and account of the day are dealt with here.

Just prior to the day, Harvey claimed, he provided information that SWP members had deposited bricks alongside the planned route of the march to be thrown at the fascists the next day. ‘Madeleine’ challenged whether it was SWP members doing this. However, whether accurate or not, Harvey voiced frustration that A8, the police public-order unit, did not use his information to control the counter-demonstrators’ plans.

Harvey recollected:

The night before, I turned up with the SWP to plan the counter demonstration. Some members of the SWP deposited bricks at strategic locations to use the next day. I called the office at about 2 am and gave the locations of where the bricks were stashed and where the route should be directed. I also gave intelligence on the number of SWP demonstrators. I suspect a composite of these details were passed to A8.

The next day I travelled back to Lewisham arriving mid-afternoon, The NF were on their march and had large union jack flags and bands playing. The SWP proceeded with their counter demonstration which soon turned violent. It was absolute chaos. I was surprised because the police did not re-route the NF march. This enabled some SWP members to obtain and throw the stashed bricks at the police, who were trying to keep order.

In his oral statement, Harvey suggested that the SWP wanted a confrontation with the NF. However, the route the National Front chose to march aimed to intimidate or provoke one of south London’s most diverse neighbourhoods. The SWP and many other groups took the view that the march needed to be stopped, as a threat to community safety. The scale of opposition to the march has been credited with slowing, if not halting, the progress of the National Front.

Harvey said he did not get involved in the disorder himself and, despite his claimed involvement with stashing bricks, maintained that he had guided his group ‘away from the violence’.

The SDS 1978 Annual Report stated that the squad’s intelligence greatly assisted in planning the demonstration. However, Harvey doubted whether his reporting leading up to the event had much impact, as ‘the police took a hammering during that demonstration’.

Harvey admitted having had four sexual relationships while undercover. The only one closely examined involved the woman who used the pseudonym ‘Madeleine’ in the context of the Inquiry.

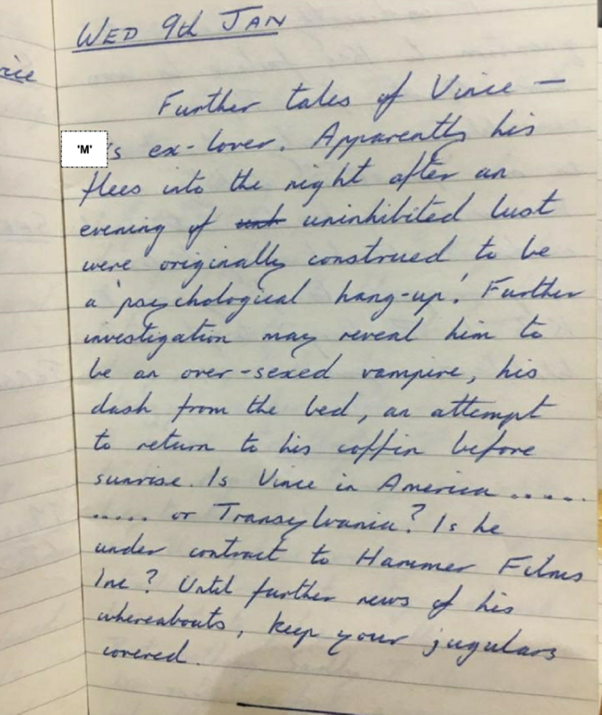

‘Madeleine’ and Harvey disputed the facts of the relationship. She said their relationship lasted approximately two months: Harvey claimed it was a one-night stand. However, ‘Madeleine’ was able to give a detailed account of how their friendship developed into a sexual relationship that lasted up to two months.

The Inquiry heard documentary evidence from the diary of a friend of ‘Madeleine’, which referred to Harvey as her ex-lover, suggesting a longer relationship.

Julia Poynter, a SWP Walthamstow member at the time, also provided a written statement supporting ‘Madeleine’s’ account of the relationship. She said:

‘Madeleine’ and I confided in each other about our personal lives, including our relationships. I remember ‘Madeleine’ discussing her relationship with Vince with me. I recall that I knew that it was a sexual relationship and that she liked him a lot. It was clearly not a one-night stand.

‘Madeleine’ described spending time with Harvey in the pub and after SWP meetings. She said she confided in him and believed at the time that he had reciprocated. She added that she was ‘devastated’ when the relationship suddenly ended. The harmful impact of finding out her former partner was an undercover police officer is detailed in her written and oral evidence.

Julia Poynter also recalled that it was clear to her ‘that it had been a significant relationship for ‘Madeleine’ and that she was upset about the relationship ending’. ‘Madeleine’ also spoke of feeling betrayed, vulnerable, and disgusted. Harvey countered that to use the word ‘betrayal’ was a little over the top.

The Chair of the Inquiry stated that he found ‘Madeleine’ an honest witness. Harvey, who gave evidence after the Inquiry heard from ‘Madeleine’, was asked to explain why his telling of the relationship differed from the accounts that ‘Madeleine’ and Julia Poynter had given.

Harvey could not offer much, other than to say that his memory was incomplete. When Mitting pushed Harvey to explain, he suggested that ‘Madeleine’ sought to damage his reputation – and that of the SDS – in saying that the relationship was longer term.

Attendees at Harvey’s hearing noted the discomfort he displayed when giving evidence about his relationship with ‘Madeleine’.

Harvey also claimed that around 1978, before he entered into any sexual relationships while working undercover, Poynter made sexual advances to him. He claimed he told HN34 Geoff Craft about this, and Craft had said that engaging in a relationship would not be a good idea. Craft said he did not recall this at all.

Julia Poynter also vehemently denied making any such advances.

Other relationships

Harvey also admitted to having had sex with another east London SWP activist just before his deployment ended. Counsel to the Inquiry put it to Harvey that neither 'Madeleine' nor the unnamed activist would have consented to have sex had they known he was a police officer. Harvey accepted this was true.

Harvey admitted having had sex with two other women while deployed undercover. He said these occurred before the relationship with ‘Madeleine’, during his first months of deployment. He said he met the women casually and could not explain why he chose to pursue them. On one of the relationships, he said:

It was somebody else who I had met in a pub, trying to establish some sort of local knowledge. The pub had other people in there. You get introduced. Not my greatest moment.

Harvey later admitted having been in a long-term relationship in his real identity when he had these first two brief relationships. He also stated that he had turned down sexual advances from a male member of the SWP.

Although Harvey admitted that he had sexual relationships during his time in the SDS, he did not admit to knowing that other SDS undercovers also had them. He did agree with HN304 'Graham Coates' , who had said that, given the mentality of officers such as HN297 Richard Clark ‘Rick Gibson’ and HN300 ‘Jim Pickford’ , sex with members of the public was inevitable. Asked about the SDS’ general attitude toward women, Harvey denied there was any sexist talk in the SDS safehouse.

In addition to industrial issues and anti-fascism, Harvey’s reporting reflected other matters discussed at the Walthamstow branch meetings.

These included policy positions, such as that on the bombing campaign of the Provisional IRA. According to Harvey, the SWP’s position was ambiguous, as expressed in those meetings. He stated that:

[the SWP expressed] support for the Provisional IRA but remained critical of that organisation’s policy of random bombing of working-class people.

However, ‘Madeleine’ said in her written statement that this was inaccurate and that the SWP’s position was that it did not support the PIRA’s bombing campaign, whether the target was civilian or military.

‘Madeleine’ also challenged various aspects of Harvey’s reporting on her and on the Walthamstow branch. She questioned how Harvey was justified to report, on 11 July 1978, the details of her previous marriage:

It records the fact of my marriage 2 years earlier and details the address where I lived with my husband. Why was my marriage any business of Special Branch or MI5?

‘Madeleine’ had similar questions about why a report detailed her employment as a bus conductor.

Harvey said he never had any direct contact with MI5. However, his deployment was discussed at MI5 meetings involving SDS management. MI5 asked surprisingly detailed questions about the dynamics and policies of the Walthamstow SWP branch.

This included a request for a day-in-the-life account of a typical SWP member:

How much time/effort is demanded and given by local members to the cause? How much effort is made by branch treasurers to extract membership dues according to the letter of the new(ist)scale of dues payable according to age/income, or do many members get away with paying less then they should? How well do special appeals like the appeal fund against the Tories?

A ‘debrief’ for Harvey was mentioned in another MI5-authored document after his withdrawal from the field. However, it does not seem that MI5 debriefed Harvey, even though the agency did debrief other SDS officers such as HN106 ‘Barry Tompkins’.

Harvey recalled that requests came regularly from MI5, and that nearly all SDS reports were copied to the agency. This included, in a report dated 7 December 1977, a full list of the SWP’s members.

Harvey said when he started to withdraw from the deployment, he was studying for a police promotion exam, having been selected for a ‘fast-track’ programme. During the interview for the promotion, he was questioned why he had long hair and a beard.

The story that he told the SWP was he had a plane ticket to the US and that he and a friend were going to ‘follow the music scene’:

I remember telling a member of the SWP that we had obtained a six-month visa. He replied that that was impossible, so I had to come up with a story about my friend arranging the visa. I told my group that I would overstay in the USA.

This is mentioned in a Special Branch report on the branch dated 25 September 1979. It seems that by November 1979, Harvey had finished his deployment. He said he also continued to contact his target group, sending postcards from the United States.

After Harvey completed his course in December 1980, he joined C Squad as a detective sergeant, where he was placed within the ‘right-wing section’.

In 1981, he was promoted to the rank of inspector, where he was one of the senior officers in charge of a uniformed patrol based at Paddington Green police station, where IRA and other terrorist suspects were held. Harvey asked to be removed from this post as it was often picketed by members of the Troops Out Movement , who were SDS targets and who might have recognised him. The request was refused.

Between 1982 and 1985, with police sponsorship, Harvey studied social psychology at the London School of Economics. He then returned to C Squad at the rank of detective inspector. This was his final post within Special Branch.

Promotion followed to detective chief inspector in April 1987, when Harvey took an MBA at Warwick University, which he completed in October 1988.

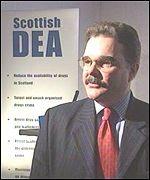

Next Harvey was posted to Wimbledon police station from February 1990 until December 1991 when he became the staff officer to a deputy assistant commissioner. In December 1992 he became ‘area’ detective chief inspector. He then joined Kent police as a superintendent. After Kent Police, he moved to the National Crime Intelligence Service (NCIS), becoming national director with the equivalent rank of a commander before he retired.

As one of the top NCIS officers, Harvey made several media appearances. The revelation that he reached such a senior position within the police has sparked questions, from the media and from the many people affected by Harvey’s deployment – not least why the Inquiry sought to keep his real name a secret.

Operation Pragada

While a detective chief inspector, Harvey was appointed by deputy assistant commissioner Ian Johnstone to investigate allegations that Lambeth Council employees were involved in making and distributing child pornography. Operation Pragada ran from 1993 to 1994, the second of four investigations of sexual abuse of children in the care of Lambeth Council.

The police investigation headed by Harvey came under substantial criticism during the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA), which said ‘that detectives missed opportunities to identify networks and links between offenders’.

On 29 November 2017, the Metropolitan Police applied to restrict Harvey’s real name only. On 19 June 2018, Harvey’s cover name and target groups were published by the Inquiry.

An application by the Metropolitan Police to restrict HN354’s real name was granted on 30 July 2018. A decision to revoke this order was made on 30 March 2021 due to the details that ‘Madeleine’ supplied in her written statement about their sexual relationship.

Harvey submitted a written statement to the Inquiry on 18 November 2019, supplementing this on 10 March 2021 in response to ‘Madeleine’ detailing the duration of their sexual relationship.