Trevor Butler served as a Special Branch officer from 1968 until his retirement in the late 1980s or early 1990s. He joined the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) as second-in-command with the rank of detective inspector in 1979, eventually becoming the head of the unit as a detective chief inspector from May to December 1981.

According to Butler, his role as detective inspector involved mainly personnel matters, rather than operational issues related to SDS targeting of specific groups.

Butler claimed that the primary purpose of the SDS was public order and, despite contradictory documentary evidence, he said that providing information to MI5 was not a significant part of the SDS’ role. Regarding Special Branch reporting, Butler defended the practice of recording seemingly extraneous and personal details about individuals, claiming these details had ‘latent value’.

Butler recalled various events from his time, including protests at the Torness nuclear reactor in 1980, the Right to Work marches organised by the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), and direct actions carried out by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

He stated that he was unaware of any sexual relationships between undercover officers and members of their target groups at the time.

Butler submitted a written statement dated 17 March 2021 and appeared before the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI) on 20 May 2022. Unless noted otherwise, all references pertain to Butler’s written statement.

Trevor Charles Butler was born in 1942. He joined the Metropolitan Police service on 21 October 1963 and Special Branch on 8 April 1968. As is usual in a Special Branch career, Butler worked across most sections.

He initially spent 18 months on B Squad enquiries, where he completed his probationary period. This would have involved monitoring left-wing groups, including attending meetings and protests in a plain-clothes capacity, particularly those concerned with the anti-Vietnam War demonstrations.

From October 1969, Butler worked in E Squad for two years. In September 1971, he was sent to C Squad , which had taken over the old B Squad responsibilities. He was then promoted to detective sergeant. Following ten months on C Squad, he was placed on port duty until June 1975, when he returned to B Squad, which then focused on Irish issues.

After police-corruption scandals earlier in the 1970s, all detectives were required to return to uniform duty. As a result, Butler spent a year at Barkingside Police Station. He returned to MPSB in July 1978 back on C Squad.

After he took his inspector’s exam in the summer of 1979, Butler was summoned to the S Squad office.

Two senior officers, detective chief superintendent HN819 Derek Kneale and detective superintendent HN608 Kenneth Pryde , told Butler he had passed the exam with the highest grade and offered him the job of second-in-command of the SDS, which he accepted ‘with no hesitation’. He later headed the unit as a detective chief inspector between May 1981 and December 1981.

Duties as a senior SDS officer

In both his written and live evidence, Butler disavowed responsibility for several key SDS operational matters, such as preparing a UCO identity and arranging officers’ cover documents, exfiltration and accommodation. Butler said he was more involved in the welfare of officers, including their physical fitness and preparing them to take their sergeants’ exams. On his welfare role he said:

I used to play [[Gist: sport]] with each UCO regularly and tried not to leave much longer than a month between our meetings. This allowed them to raise any issues with me and will enable us to have a general discussion. Unless required by other duties, I was also at a twice-weekly safe-house meeting. The first half-hour of one meeting a week was set aside for a properly structured class for promotion candidates.

Butler agreed he had a role in recruiting undercover officers but could only recall selecting HN65 ‘John Kerry’ and HN85 Roger Pearce ‘Roger Thorley’.

He also said he felt under pressure from his senior officer, chief inspector HN34 Geoff Craft , to reduce the amount of overtime that undercover officers were paid.

Signing Special Branch reports

Butler asserted he had no role ‘in writing or assessing UCOs’ reports’ and only started signing them when he took the more senior chief inspector’s role. This seemed to be the only difference in his duties between being inspector and chief inspector. Even in the more senior role, he rejected holding ultimate responsibility for the content, despite ostensibly authorising it:

My signature on a report indicates approval only in the loosest sense: I did not add to, edit or comment upon reports in any way. It was for others to collate the information and assess the value.

Butler also commented on the distribution of reports and the filling-in of minute sheets, which were attached as cover sheets to the reports, and discussed the flow of SDS intelligence – noting that all reports would have been routed via S Squad for onward dissemination.

SDS annual reports

On the SDS annual reports, Butler said that his signature at the end of the reports for 1979, 1981, and 1982 indicated he was responsible for their contents. However, he said he did not create the first draft and that his role was just editorial – and he would certainly not have compiled ‘the lists of groups or the summaries for the main groups covered’.

This was probably the most crucial part of the reports. Despite this, Butler was confident that the lists were accurate and did not overstate the SDS’ capacity, commenting:

As far as I was concerned then and now, the SDS provided a terrific service, trouble-free.

Targeting

Butler admitted that the targeting of groups was restricted to left-wing groups. He added that there was a geographic element in the targeting.

He said he ‘can only think of one [redacted] UCO who was tasked into a specific group’. This seems to support the argument that the SDS’ role was to monitor the activities of the left in general and was not led by any particular concerns about public order or by other matters relevant to the police.

Butler also admitted that there was ‘occasionally some trial and error involved as some groups turned out to be of peripheral importance from an intelligence perspective, despite their publicity’.

In his written statement, Butler suggested that a metric for measuring the efficacy of the SDS should be ‘based on UCOs accurately forecasting events with potential public-order implications and maintaining their cover’. He suggested that:

Against those two yardsticks, UCOs were uniformly successful in infiltrating Trotskyist, Marxist-Leninist and Anarchist groups. The ‘pro-Irish’, Anti-Fascist and Anti-Nuclear groups (with the exception of CND) were largely front organisations for the main Trotskyist and Marxist-Leninist groups or were affiliated with them in some other way.

Institutional bias and the far right

During the Undercover Policing Inquiry, lawyers for non-state core participants questioned the SDS’ lack of coverage of the far right. Butler agreed that:

During my time with the SDS, our focus was primarily on public order and on the extreme left-wing and anarchist groups. This was not a question of political bias, in my mind, but rather that these groups had sufficient mass as to pose a threat of disorder.

Butler claimed the ‘extreme right-wing and race-based groups did not attract the numbers or demonstrate the same level of risk’ and added there was no direction from more senior managers within MPSB to target the far right. Like other officers, Butler added a perverse justification for only targeting the left, saying:

the greatest risk of extreme right-wing groups becoming involved in public disorder and violence occurred when there were confrontations between them and the extreme left.

During the hearings, lawyers questioned a phrase in the 1980 SDS annual report: ‘Anti-fascist activity continued to tax the resources of the Metropolitan Police’. Butler suggested that, at the time, it was felt that those on the left were more likely to instigate trouble.

Activist witnesses made the point, giving evidence, that this ignored the fact that counter-fascist mobilisations were reacting to large-scale National Front marches, often through areas where migrant communities were being targeted in racist attacks.

Perhaps more convincingly, Butler said that Special Branch saw clashes between anti-fascists and fascists through a Cold War lens:

It should not be forgotten that the Cold War was still in progress and there was, at the time at least, real fear of extreme left-wing groups providing assistance to the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact in the event of any conflict in Europe.

Torness

Butler drew again upon the 1980 SDS annual report to justify SDS operations by highlighting the SDS infiltration of the Torness Alliance by HN155 ‘Phil Cooper’ via London-based groups. This was a nationwide network of activists who opposed the construction of a nuclear power station in Torness, Scotland. Butler said this deployment helped to prevent criminal damage and disorder at the nuclear power plant in Scotland.

However, while there are reports from planning meetings regarding a week of planned protest at Torness, the Inquiry did not locate any reports about the week itself. Butler also mentioned going to Torness to support Cooper on one or more occasions.

Right to Work marches

Butler also cited two instances of SDS assistance in effective policing of the 1980 and 1981 Right to Work marches. The Right to Work marches, organised by the International Socialists (later the Socialist Workers Party), first took place in 1972. These consisted of groups staging a rolling series of organised marches across Britain, sometimes concluding with a big rally.

As with most demonstrations organised by the IS/SWP, these marches had a well-publicised schedule, so it is unclear what relevant information the SDS could have added to these publicly advertised events. The only recorded instance of public disorder on these marches occurred in 1976 when the march passed through Hendon and was attacked by the police.

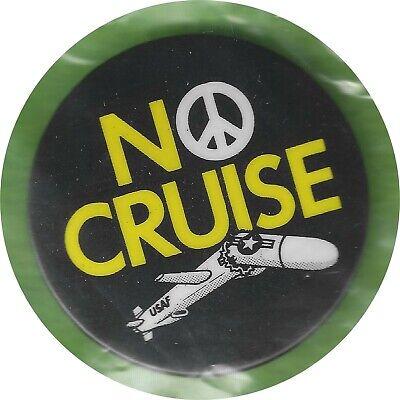

CND

Another example Butler gave was advance notice of the ‘potential subversion of CND activities through the use of direct action against cruise missile deployments’. It is unclear what Butler meant by this as, clearly, acting against nuclear weapons was central to CND activities or policy. Butler was probably referring to the direct action favoured by ordinary CND members and by other groups such as the Greenham Common women’s peace camp.

Reporting personal information

Many Special Branch reports included – and sometimes exclusively concerned – details about the personal lives of campaigners beyond their political activism.

Butler addressed several reports that highlighted this issue. For example, a HN96 ‘Michael James’ report discusses the breakdown of a romantic relationship between two members of the Walthamstow branch of the Socialist Workers Party. Butler sought to legitimise the interest in the couple’s relationship by saying that their break-up might have impacted the group’s activities.

He also attempted to justify the interest by saying that ‘one of the couple had an Special Branch Registry File already open on them, so they must, therefore, already be of some interest’ and so ‘it had value for keeping the files up to date’.

During the hearing, Butler was questioned about his statement that the ‘second most important contribution’ the SDS made, after public order, was ‘the provision of information to update MPSB files’. Asked what intelligence in the Special Branch registry was used for, Butler instead described what was in the files and explained the police procedures for managing the paperwork.

Counsel for the Inquiry (CTI) pressed Butler, asking what this information could be used for that made it an important contribution. As before, Butler was unable to answer, admitting that the information may not have been immediately useful.

The CTI also introduced a report on the Freedom Collective that had copied the exact contents of a member’s address book. Some names are listed alongside their – redacted – registry file numbers. However, out of some 40 names, 14 have the letters N/T written alongside, indicating that there was ‘no trace’ of these names in Special Branch records.

Asked whether it was standard practice to retain the names on the document even when people had no previous Special Branch mention, Butler said:

The fact that they were ‘no trace’ at that stage didn't preclude them from becoming people of interest, so it may well have been retained on a general file, yes.

He added that such information might have ‘latent value’:

Not all the information that MPSB obtained and recorded had immediate intelligence value but occasionally it had a latent value, and he [the UCO] would have lost nothing if it later turned out not to be important.

Counsel to the Inquiry also asked Butler about several reports that recorded seemingly irrelevant personal details. These included whether or not a marriage had been ‘consummated’ and the fact that one person in the couple suffered from cystitis.

Butler agreed that some of the detail was ‘not necessarily relevant’ but suggested that information about the marriage might reflect that the group was alleged to engage in sham marriages. Another report noted that an individual member of the SWP was gay. Butler suggested that, as being openly gay was less common then, this detail might have been useful for identification purposes.

Two other reports were also raised, reporting on the memorial service of CND member Betty Keeping and, separately, on the funeral of Communist Party of England M-L chair Cornelius Cardew. Butler admitted that these reports ‘may appear distasteful’ but said it was necessary to keep the files updated and closed.

It would not have been necessary for the undercover officer to attend the funeral to close Cardew’s file. Butler countered that the funeral of Cardew might have been significant as it ‘appears to have political overtones’.

Yet another report focused on a CND campaigner who had moved address. The report noted that the campaigner was single but insinuated that he was sexually active. Butler agreed that the latter information might seem ‘gratuitous’ but speculated that it ‘could follow on from previous reporting and may have been thought a relevant feature of the individual’s profile’.

Perhaps missing the point, Butler added: ‘I do not doubt that the officer [writing the report] did not imagine it would be subject to public scrutiny nearly forty years later.'

Butler told the Inquiry that although the reports contained some content that ‘may seem unacceptable in today’s context’, they were the unavoidable part of the British state wanting to ‘keep a record of potential extremists and activists’. He continued:

I do not believe that individuals finding their names on a Special Branch or Security Service file is too high a price to pay for comprehensive intelligence coverage, providing that those individuals were not unlawfully discriminated against because of this.

Butler stated that he knew nothing about UCOs having sexual relationships during or outside his time in the SDS, adding:

they were married men with a stable background who I trusted not to get involved sexually outside of their marriage.

He did admit there was sexual banter in the safe house.

Contradicting his position is the accusation made against HN106 ‘Barry Tompkins’. Tompkins was suspected of a relationship with one, if not two women, partially based on an MI5 telephone intercept.

Notably, Tompkins stated that it was Butler who confronted him with MI5’s information that he had ‘bedded’ a woman. Butler vehemently denied confronting Tompkins. In his witness statement, Butler said that had he known that Tompkins was, or might have been, having a relationship outside of his marriage:

I would have reminded him about his obligations to [his family] and to the job in fairly strong terms if I had even the slightest suspicion that he had [been] or was tempted to stray.

Counsel to the Inquiry put it to Butler that this demonstrated consideration of the impact on the officer’s marriage, and of the risk to both the SDS and the wider Met; it showed none for the woman Tompkins had formed this close friendship with. Butler confirmed that he would not have given her any consideration.

Other officers who had sexual relationships during Butler’s tenure as SDS manager were HN354 Vincent Harvey ‘Vince Miller’ , HN126 ‘Paul Gray’, HN155 ‘Phil Cooper’ and HN21.

Butler also denied knowledge of similar allegations relating to HN300 ‘Jim Pickford’ or that he knew that HN67 ‘Alan Bond’ had fathered a child while on deployment.

Counsel asked Butler whether he still held the view that, as he said in his written statement, ‘the SDS provided a terrific service, trouble-free’.

Butler said he did not want to rush to judgment but was ‘disappointed’ to find out about the ‘affairs’. He added that had he, or more senior officers, known about the relationship, it would not have been clear whether disciplinary action would have been taken due to the risk that this could compromise SDS operations.

During the Inquiry hearings, witnesses discussed the main purpose of the SDS. In the main, senior officers and counsel for the Metropolitan Police maintained that its primary purpose was public-order policing. However, the Inquiry also heard substantial evidence that much of the unit’s work was for and or directed by MI5.

Butler disagreed, saying:

Any assistance that the Security Service derived from the UCOs was incidental to their deployments, albeit they would try to respond to requests for information where they could.

This stance differs from the corporate view expressed by Butler’s lawyers, who noted close cooperation between the SDS, Special Branch and MI5. It also minimises the number of meetings Butler held with MI5, on which the latter kept notes.

At several such liaison meetings, Butler and other SDS officers discussed ‘issues of mutual interest’ – normally political groups and individuals within those groups – and Butler is recorded by MI5 to say that he welcomed feedback on how useful the agency was finding the SDS reports.

In a related point, Butler maintained that inquiries from MI5 would have come via S Squad and not directly to the SDS. Again, this stands at odds with the meetings between SDS managers and MI5, which featured such requests and which Butler personally attended. MI5’s requests included asking for more information on one group and chasing up a report on a specific meeting of another.

While Butler agreed that the ‘MPSB and the Security Service had a close relationship’, he qualified even this, emphasising that ‘MPSB and the wider MPSB, A8 in particular were the unit’s primary customer’ and that any assistance to MI5 was ‘largely collateral’.

Butler continued:

Even if we did provide intelligence ‘to order’ for the Security Service, that was still of benefit to the Branch, and one of its functions was to support the Security Service.

He was also asked a question about a third group, CND , that, during the 1980s, held large demonstrations across the country, especially in London. Counsel pointed out that although CND demonstrations were large, they were ‘extremely well stewarded and entirely peaceful’.

Butler agreed, but added that these marches:

were quite often infiltrated by extremists who wanted to use their well-organised demonstrations for their own purposes.

Counsel to the Inquiry countered that ‘[the] actuality was that they weren’t causing public disorder […]’ and asked:

[was] the mere possibility that somebody might try and incite a group which was stewarding perfectly orderly demonstrations really sufficient fully to justify infiltration to preserve public order?

Butler then changed tack, saying that groups like CND were surveilled ‘incidentally’, not because they were a target themselves but because ‘they attended the same meetings or demonstrations as the groups the SDS officers were covering’.

Challenged that this was not true in the case of CND, as undercover HN65 ‘John Kerry’ had been deployed to infiltrate the group during the early 1980s, Butler countered that Kerry’s infiltration began when he was leaving the SDS and so had no personal dealings with CND. Butler’s answer ignores the fact that he would probably have assigned Kerry’s tasking.

On leaving the SDS in early 1982, Butler went to the National Joint Unit and B Squad until 1985.

Butler then went on to protection where he spent the rest of his career. Butler added that after retiring from the MPSB, he worked with former Special Branch colleagues for a time but did not specify in what way.

No anonymity application was requested on Trevor Butler’s behalf. His name was published during the Tranche One hearings in 2020. Butler provided a written statement dated 17 March 2021 and appeared before the UCPI on 20 May 2022.