David (Dave) Smith, born in 1939, began his career with the Metropolitan Police in 1959 and joined Special Branch in 1962, where he worked in roles including public order, telephone bugging and bodyguarding. He joined the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) in October 1970 as its first office manager, handling administrative tasks. He played a crucial role in the withdrawal of undercover HN68 'Sean Lynch' after a possible compromise of his cover identity and helped manage other similar incidents.

After leaving the SDS in October 1974, Smith monitored far-right activities before being promoted to inspector, continuing his work in naturalisation, protection and Irish matters until 1979. Following a brief rotation out of Special Branch, he returned in 1981 as chief inspector on C Squad, focusing on animal rights and right-wing issues.

In 1988, he became chief superintendent of C Squad, overseeing the SDS. He retired in October 1989. Smith provided a written statement to the Inquiry on 2 December 2020 and may be asked to provide further evidence about the latter part of his career. Unless otherwise cited, the material in this profile comes from his witness statement.

Disambiguation: There is another 'Dave Smith' involved in the public inquiry. Dave Smith, who is a core participant due to his involvement in the Blacklisting Support Group and being spied-upon by Carlo Sorrachi and Mark Jenner.

Born in 1939, Smith joined the Metropolitan Police in February 1959 and moved to Special Branch in August 1962. Smith describes his deployments prior to the SDS as naturalisation, C Squad , telephone interceptions, protection work and E Squad.

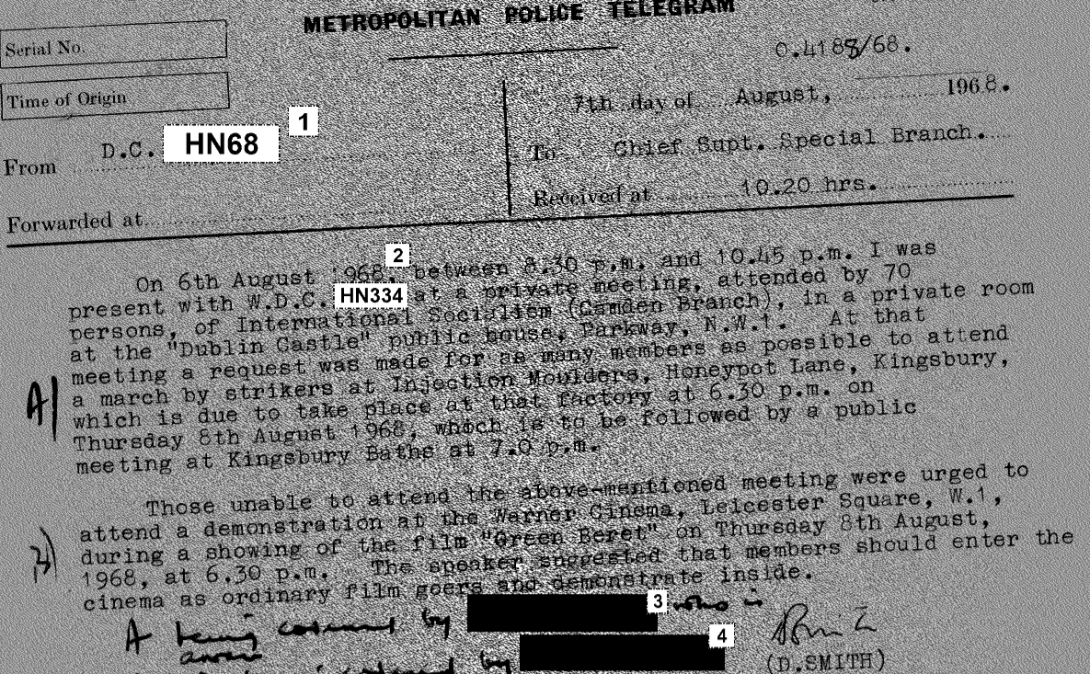

Smith said his time in E Squad was spent monitoring the far right, but prior to 1969 this was carried out by B Squad; E Squad monitored ‘Foreign Terrorism and Extremism’. There is also one document published by the Inquiry which relates to detective sergeant Smith prior to him joining the SDS. It is a telegram dated 7 August 1968, regarding an International Socialists meeting.

Smith was invited to join the SDS by its head HN1251 Phil Saunders , who offered him the role without an interview. His previous experience on C Squad meant he knew the political targets that the SDS focused on. He was aware of the unit’s existence, saying it was common knowledge that HN325 Conrad Dixon had set up a unit of undercovers, known as the ‘hairies’.

He understood the SDS came to be formed in response to the events of the March 1968 anti-Vietnam war protest and the Grosvenor Square riot:

There was a choice of either escalating the number of police at such events and resorting to the use of things like rubber bullets, water cannons or tear gas or utilising intelligence to better police such events.

Smith elaborated on these views in an essay he wrote on policing public disorder as part of a training course he attended in 1979.

The back office

David Smith’s involvement with the SDS was at a relatively low level, administrating the back office which at that time was based at New Scotland Yard. He was the first SDS office manager. He describes a good working relationship with his bosses, with whom he shared the office.

Unusually, he appears to have been alone in this job, except between July 1972 and March 1973. In general, as working in the back office was a key part of preparing future undercovers, Smith was assisted by a number of those awaiting deployment during his time.

His own work was a continuation of the administrative work he had already been doing within C Squad – receiving paperwork from undercover officers and processing it.

Smith did not regularly attend the weekly meetings at the SDS safehouse, which was the job of the managers such as Phil Saunders, HN332 Cameron Sinclair or HN294. However, he did visit the safe house once a month – sometimes for a social event or to take some files.

Importantly, he notes that other parts of the Metropolitan Police knew of the SDS and passed requests to undercovers through him. These would include photos of ‘potential targets’ for undercovers.

Another role was to attend significant demonstrations, usually two or three per month, in plain clothes. After such demonstrations he would return to the SDS office to take phone calls from undercovers who would confirm their wellbeing and pass on information on who had been present.

One of his responsibilities was the finances of the unit, and he oversaw the distribution of rent money to the undercovers. He was not involved in the tradecraft side of the undercover deployments.

According to Smith, MI5 would send letters requesting information, usually about individuals, especially ‘new members and what was known about them’. However, these requests came through other Special Branch squads who then passed them on to the SDS if needed.

One document shows Smith having taken the minutes at a high-level meeting between Special Branch (including the SDS) and MI5 in 1972 which reviewed where the two organisations overlapped in their coverage of left-wing groups.

Incidents during his tenure

Smith provides an account of his role in the exit of HN68 ‘Sean Lynch’ , who was a long-serving undercover who infiltrated Sinn Féin in London. Both Detective Chief Inspector HN819 Derek Kneale and the detective inspector at the time, probably HN3378 Derek Brice , were away so Smith was directly involved.

Lynch reported that a uniformed police officer had recognised him and indicated in front of genuine activists that he was a police officer. Smith recalled that he and a more senior Special Branch officer decided to withdraw Lynch immediately. Smith also remembered HN339 ‘Stewart Goodman’ being arrested for drink-driving.

Another incident Smith had to deal with concerned the publication of a photo of HN340 ‘Andy Bailey’ in 1972 competing in a sporting event. Smith was tasked with asking the undercover to come to New Scotland Yard to talk to concerned managers, though he believes his only role was as a messenger.

Star and Garter

On 12 May 1972, during Smith’s time as SDS back-office sergeant, HN298 ‘Mike Scott’ was arrested as part of the Star and Garter incident, when anti-apartheid protesters blockaded the exit to a pub car park to stop the South African rugby team leaving. This eventually led to a trial and 14 convictions in which Scott and the others were convicted and fined.

Inquiry Chair John Mitting's Interim Report confirmed that neither the prosecution or magistrates knew that Scott was an undercover officer. In 2021, three of those convictions were overturned due to the fact that Scott’s presence as an undercover had not been disclosed to the court during the trial. Inquiry core participants Christabel Gurney, Ernest Rodker and Jonathan Rosenhead had their convictions overturned.

Smith says he was not privy to the advice given to Scott by his managers after his arrest. He believes such arrests were inevitable and played down the severity of the offence:

To disclose the fact of an undercover deployment more widely risked the uncovering of the undercover officer and cumulatively would risk the uncovering of the squad over time. Generally, I understood an officer would be advised to plead guilty and pay a fine.

Despite all the incidents mentioned above Smith says there were no ‘formal measures’ for welfare but suggests morale was good within the squad. Smith was among the many police witnesses who claimed they knew nothing about any of the sexual relationships that occurred during the SDS’ existence.

Processing reports

An important part of Smith’s work was to process the information generated by the undercovers and turn it into intelligence reports. The DCI and DI would pick up handwritten reports from the undercovers at the weekly safehouse meetings and give them to Smith. He would go through them for stylistic changes, ‘or perhaps add a line to explain the context’ and then send them to the typing pool.

He says his changes were minimal, implying that the reports are essentially the words of the undercovers themselves. The reports themselves have been criticised for including personal details of those who were spied on, including sexuality, living arrangements and health issues.

Smith’s justification for this was that one might not know the relevance of these personal details until some time afterwards: what SDS officer HN307 Trevor Butler labelled the ‘latent value’ of the intelligence. Alternatively, he said it could be used to prove a negative, giving the example that the IRA were not attempting to recruit activists from left-wing groups into the armed conflict

When the reports came back from the typing pool, he would take them to SDS management to sign off, then distribute them to the relevant chief inspectors in other Special Branch squads. Each undercover had their own file within the SDS office containing all the reports they had generated.

Following his time in the SDS, Smith was promoted to the rank of inspector and held positions in naturalisation, protection and then B Squad (Irish matters) until 1979 when he transferred out of Special Branch.

He was not away from Special Branch for long, returning in November 1981 as a chief inspector on C Squad , where he was responsible for animal rights and right-wing issues. Notably, this is the period in which we see the first SDS deployments into the animal-rights movement; HN11 Mike Chitty ‘Mike Blake’ and HN10 Bob Lambert ‘Bob Robinson’.

In 1985, Smith moved to A Squad which oversaw Special Branch’s protection duties, and subsequently became a superintendent. In August 1988, he returned to C Squad as chief superintendent, where part of his responsibility included the SDS – though he claimed he was ‘not involved in the day-to-day management of the squad at that time’.

Smith was aware that SDS intelligence was being passed to C Squad for use in its threat assessments. He retired from the Metropolitan Police in October 1989.

Smith’s essay on public disorder

Smith shared an essay he wrote in 1979 on policing public disorder with the Inquiry. In it, he reveals his thoughts about a number of issues, including undercover policing, public disorder, and police attitudes at the time.

In the Inquiry, one of the issues that ran throughout the hearings was the bias of the SDS targeting policy – where no groups on the far right were targeted in 1968-1982 in contrast to the hundreds of groups on the left. In his essay Smith gives the impression that the same bias also existed within policing in general:

The Fascists... are nearly always co-operative and whenever possible try to align themselves with the police in their support of law and order to the extent of quoting this co-operation as a justification of their policies.

Smith continued:

Rather like the Communist Party of Great Britain, they [the fascists] are courting respectability as a matter of policy, so police should never be lulled into forgetting the true nature of their character.

Despite this, Smith also opined that ‘Trotskyist’ groups were the most violent on demonstrations. He pointed to events in Red Lion Square in 1974 and the Grunwick dispute of 1976-1978 as examples of ‘premeditated violence’ on behalf of these protesters. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Smith does not consider police tactics as a possible cause in terms of the violence.

Smith also gives some insight into how intelligence received from covert sources on plans which might become public-order incidents can be utilised without compromising an undercover officer’s, or civilian informer’s, identity:

For example, it may be known that the International Marxist Group plans to hold a six man 'sit-in' at an Embassy and knowledge of this is confined to a few 'trusted' supporters. Clearly, if police are found to be waiting for the would-be participants it would pose very serious problems for the source. Similarly, if the 'sit-in' is allowed to continue it might prove to be embarrassing politically. A solution is to acquaint uniformed police of the problem and to arrange for sufficient officers to be in the vicinity so they can respond to the call of a 'coincidentally passing officer at the start of the 'sit-in'.

No application for a restriction order was made on behalf of David Smith’s real name and he did not use a cover name. Though he gave a written statement to the Inquiry on 2 December 2020, Smith was not called to give oral testimony during the Tranche 1 hearings. However, he may be approached again by the Inquiry in relation to his subsequent roles at C Squad where he was in the SDS’ line of management.