HN34 Geoffrey Craft was born in 1937. He began his career as a Special Branch officer from 1962. He served as a Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) manager, as both inspector and then chief inspector, from 1974 to 1977. Between 1980 and 1983, he was chief superintendent in charge of S Squad, where one of his primary responsibilities was overseeing the SDS. He retired in 1986 with the senior rank of chief superintendent.

Craft submitted two written statements dated 7 December 2020 and 23 February 2022. He appeared as a witness at the Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings on 18 May 2022.

All citations are from Craft’s first written statement unless otherwise specified.

In the Inquiry Interim Report, published on 29 June 2023, the chair John Mitting concluded that Craft was an ‘honest witness’. However, non-state participants thought Craft’s memory lapses on important events undermined his credibility. These predominantly concerned two separate issues; lack of awareness of undercover officers’ sexual relationships and of miscarriages of justice.

Other issues raised by Craft’s evidence include the coherence of the SDS’ targeting policy and the disproportionate attention that undercover deployments paid to left-wing groups compared to those that targeted the far right.

This is pertinent given that Craft’s time with the SDS coincided with a peak in National Front activity, both electorally and on the street, including notorious clashes at Red Lion Square in 1974 and at the so-called Battle of Lewisham in 1977. The two events bracket Craft’s time as an SDS manager.

Craft started his police career as a cadet aged 18 and became a Metropolitan Police constable in 1956 on his 19th birthday. He spent five years in uniform, until 22 January 1962, when he joined the Metropolitan Police’s Special Branch.

His first posting was as a temporary detective constable to D Squad (Immigration). After approximately a year, the time it took Craft to become a full detective constable, he moved to C Squad ‘to do far left enquiries’ and served around six months in 1963 at Folkestone on Ports duty.

Craft then returned to C Squad, where he said he was ‘involved a lot in Official Secrets Act cases’. He was promoted to second-class sergeant in May 1965 and to first-class sergeant in October 1968 while on B Squad, before a further Ports duty posting to Dover in March 1970.

IRA Aldershot Barracks Bombing

Of his time with B Squad, Craft said:

I had benefited from the SDS in 1972 when the official IRA blew up the parachute barracks at Aldershot. I was on the team investigating the bombing, and somebody who had been on the SDS, because of the nasty people he was working with, came up with a couple of names of people he thought might have moved into the official IRA. He put his finger on Noel Jenkinson. The intelligence which pointed us in Noel Jenkinson's direction came from the SDS …

Noel Jenkinson was jailed for his involvement in the bombing in November 1972, which the Official IRA said was in revenge for Bloody Sunday. Jenkinson was also involved with Clann na h’Eireann , an Irish-emigrant support organisation that was part of umbrella organisation the Anti-Internment League , which had been infiltrated by the SDS from its founding in 1971.

This claim makes Craft’s account plausible, although it is unclear which officer would have provided the information. The candidates would be HN68 ‘Sean Lynch’ , HN344 ‘Ian Cameron’ or HN340 ‘Andy Bailey’.

Craft then spent a year on bodyguarding duties, protecting the Conservative home secretary Robert Carr from 1973 until February 1974. Carr had recently been targeted in an attack by the Angry Brigade.

Craft says he was recruited into the SDS ‘as the No. 2’ to chief inspector HN819 Derek Kneale in early 1974. The pair were promoted a little more than a year later, Kneale leaving the squad and Craft staying as chief inspector in the unit. Craft moved on from the SDS circa September 1977.

Duties as SDS manager

Craft said that the roles of chief inspector and inspector were ‘interchangeable’ in the SDS: ‘The principal aspect of this role was the supervision and care of the people in the field. We were available to them 24/7.’

He added it was normal to meet the undercover officers on a daily basis. He mentioned that he was involved in organising the promotion seminars to aid detective constables sitting their sergeants exams.

Craft added that he had a role supervising cover accommodation and safe houses, but that undercover officers and more junior back-office staff would manage the minutiae.

Role of the SDS

Craft saw the key role of the SDS to be providing public-order intelligence. However, it did not select which groups would be targeted; it largely responded to the requirements of others. In his statement, Craft gave a detailed description of how the tasking of the SDS came via C Squad and sometimes ‘Commander Ops’ of Special Branch.

Ultimately, despite a lack of day-to-day contact with the Home Office, Craft was clear that the SDS operated at the ‘behest of the Home Secretary’.

Public order and subversion

Craft recalled that the SDS’ principal stated aim was to provide information on threats to public order, and that the information it supplied to MI5 regarding subversion was secondary. How much this matched up with reality was a theme commonly explored in the Inquiry hearings, as arguably very few of the SDS’ targets presented a public-disorder threat.

The corollary is that the SDS’ role in monitoring subversion formed a much more significant and dominant role in directing the SDS’ operations than was officially acknowledged.

However, Craft maintained that public order was the unit’s main raison d’etre, recalling that when reviewing the SDS’ activities for an annual report, managers found that the unit had provided intelligence on 365 public-order activities over the year. He also stated that drafting these reports was another duty for SDS managers.

SDS Annual Reports

Geoffrey Craft had direct input into the SDS annual reports between 1974 and 1976, although he had left the SDS when the 1977 report was published.

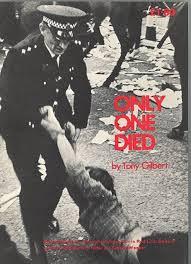

A key topic in the 1974 annual report was the confrontation involving police and left- and right-wing protesters at Red Lion Square. In 1974, the National Front held a meeting at Conway Hall in central London. A coalition of anti-fascists assembled to oppose it.

Heavy-handed policing of the counter-demonstrators led to clashes, during which a protester, student Kevin Gately, received fatal head injuries.

Although the official Inquiry into Gately’s death concluded that it was the fault of the protesters, this remains highly contested.

The 1974 SDS Annual Report said of the Red Lion Square disorder:

The most traumatic event of the year was the 'anti-fascist' demonstration on 15 June 1974, which culminated in the death of Kevin Gately. Having lacked a sufficiently interesting, broad-fronted target for some time, the 'ultra-left' eventually decided to combat the re-emerging spectre of fascism, as exemplified by the National Front.

The report similarly described the demonstration as an ‘opportunity’ for left-wing groups to cause a confrontation.

Asked during the Inquiry hearing whether SDS intelligence would have been as helpful as the annual report claimed, as the National Front meeting and counter-protests were well-publicised in advance, Craft speculated that the SDS might have provided more specific information about numbers and intentions of the demonstrators.

This echoed claims in the annual report itself:

Fortunately, the SDS gave forewarning of both the size of the demonstration and the possible disorder which might occur.

This claimed success is questionable, given that Gately died and that the disorder was deemed severe enough to necessitate a public inquiry under Lord Scarman.

Another extract from the report seemed to view Gately’s death as a positive for preventing future public-order problems:

Gately’s death introduced a note of harsh reality, so that subsequent demonstrators, both in the Metropolitan Police District and at Leicester, did not achieve the aims of the militant minority.

The 1976 SDS Annual Report

During his live evidence at the Inquiry, Craft was asked about the justifications for infiltrating various activist groups and how that was rationalised at the time, including in the SDS annual reports. The 1976 annual report became a focus for this line of questioning.

Craft stated that infiltrations of Trotskyist, Maoist and anarchist groups were justified due to public disorder, for example ‘attacking buildings and people’.

However, examples of attacks on buildings or people are notably near-absent from SDS reporting during Craft’s time.

On this point, Craft conceded that one of the groups infiltrated during his time with the SDS, the Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP) , posed no public-order threat. He suggested that the reason for the SDS infiltration was that ‘the branch was being too kind to the Security Service’.

Craft was one of the police witnesses who maintained that the SDS’ primary objective was preserving public order, and that information on ‘subversives’ was purely a spin-off. Craft also said that without the SDS deployments MI5 would have ‘had a heck of a job knowing who was involved from their [subversive] side of the house’.

In the 1976 SDS Annual Report, Big Flame was described both as ‘sinister’ and responsible for political violence in Liverpool. It said the group had connections with the Angry Brigade. However, seemingly contradicting itself, the report went on to say that ‘there is no known illegality’ connected with the group.

Craft conceded under questioning that there was an absence of hard evidence regarding violence, and the SDS only had suspicions about this.

Troops Out Movement

Elsewhere, the 1976 SDS Annual Report stated that ‘much information has been obtained through involvement with the Troops Out Movement’. This was a single-issue group, lobbying and campaigning for British troops to leave Northern Ireland.

Counsel for the Inquiry asked Craft whether, in reality, ‘much useful information has been obtained’, given that ‘TOM wasn’t seeking to overthrow the state’.

Craft struggled to justify the infiltration of TOM:

it was large at times, it was an umbrella organisation and was infiltrated or manipulated, I think probably […] by the far left.

The 1976 Annual Report was also the basis for counsel to question Craft on the justification for infiltrating other groups listed in it. For instance, it mentions how an undercover officer HN303 ‘Peter Collins’ infiltrated a splinter group of the National Front in 1975. This was instigated by the group the SDS sent Collins to spy on – the Workers Revolutionary Party – and not by the Metropolitan Police.

The report concluded that this infiltration did not add anything ‘of real value to that obtainable from already excellent Special Branch sources’. However, other sources were also available for groups on the left, namely MI5 informers and electronic surveillance.

This contrasts with the findings of a 1976 review into whether the SDS should still spy upon left-wing groups.

The 1976 SDS Working Party

In 1976, an internal Special Branch review was established to determine whether the continued operation of the SDS was still justified. Craft, then an inspector, was the most junior officer involved in the review, which also included chief superintendent HN3990 Riby Wilson , chief superintendent HN332 Cameron Sinclair and chief inspector HN819 Derek Kneale , and was chaired by chief superintendent HN1254 Rollo Watts.

The report concluded unanimously that the SDS’ continuation was merited – despite a decline in ‘violent’ public-order problems. The report said the unit was still needed, due to:

The degree of involvement and manipulation exercised by the ‘ultra-left’ in all protest organisations […] the number of splinter-groups – their unwillingness to cooperate with the police.

Craft said, on the latter point, that the only way to get information about the groups was via the SDS.

He told the Inquiry he still agreed with the report’s findings that the SDS was valuable to MI5 and Special Branch operational squads. However, he conceded that the SDS would have been primarily helpful to C Squad and that the claims in the review of the unit’s utility to the rest of Special Branch were exaggerated.

Inquiry chair John Mitting took issue with Craft’s viewpoint. In the Interim Report, he commented on the 1976 review:

It is hard to see how any conclusion could legitimately have been reached which would not have resulted in the closure of the SDS.

The Battle of Lewisham

Although Craft had left the SDS by the time the 1977 SDS Annual Report was published, it covered the period when he was in command of the unit. This included the pivotal anti-fascist counterprotest to the National Front’s planned march through an ethnically diverse area of south-east London in August 1977, later known as the Battle of Lewisham.

The 1977 report made claims about the usefulness of public-order intelligence that the undercover unit supplied to A8, the Metropolitan Police’s public-order unit, about this event. This included information that there was a house on the route of the march from which the Socialist Workers Party planned to launch petrol bombs at the National Front.

Craft was asked about this during the hearing and said this was obviously valuable information. There is no independent collaboration that such a plan existed – or any record of any related prosecution. Even in the numerous other contemporary documents, there is a mention of a property occupied, and then evicted before the march, but no mention of petrol bombs.

The Inquiry also asked Craft about a contemporary assessment written by HN1668 Les Willingale , which suggested that the public-order policing operation during the Battle of Lewisham was a failure. Craft suggested that this was because A8 needed to pay more attention to SDS reporting. For more on this, see the profile of HN354 Vince Harvey ‘Vince Miller’.

There were several undercover officers under Craft’s command during his time as a manager and questions at the Inquiry focused, in particular, on two of these.

‘Barry Loader’ – miscarriage of justice

HN13 ‘Barry Loader’ infiltrated the Communist Party of England (Marxist-Leninist). This group was involved in several confrontations with the police and the far right. Loader was arrested and appeared in court twice under his cover name. On the first occasion, in September 1977, he appeared at Barking Magistrates Court, charged with ‘threatening behaviour’.

In Craft’s contemporaneous retelling of the incident it was said that Loader had been ‘knocked to the ground’ and while ‘trying to shield two young children was somewhat battered by police before being arrested for insulting behaviour under the Public Order Act’.

A trial was set to take place in April 1978 at Barking and Loader, unlike five of his co-defendants, was acquitted.

In his written statement, Craft denied any memory of the incident. However, a series of internal police communications dating from the time proved that he had knowledge of the arrest and subsequent court appearance and that there had been direct interference with the justice process.

Faced with this documentary proof, Craft reversed this position during his live evidence, admitting that he had briefed the court clerk that Loader was an undercover police officer. Other more senior officers were involved, and the commissioner for the Metropolitan Police was also informed.

At the trial itself, Craft spoke to the clerk of the court. Superintendent HN608 Kenneth Pryde reported that court officials were:

made aware that one of the defendants is an informant whom we would be anxious to safeguard from any prison sentence should this situation arise. Duly the court official accepted this situation without demur and understanding and has been completely cooperative throughout.

At the Inquiry hearing, Craft recalled:

I briefed the magistrate that this was an undercover officer working under his undercover name, that it was a secret operation, that he would maintain that name.

This intervention resulted in Loader being acquitted, unlike his co-defendants. On 7 July 2023, the Inquiry referred the convictions as ‘suspected miscarriages of justice’, to a panel set up by the Home Office for this purpose. In May 2024, the Criminal Case Review Commission referred back to the courts, finding for the convictions to be quashed due to the undisclosed presence of the undercover officer, which it labeled an ‘abuse of process’.

Richard Clark: sexual relationships

HN297 Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’) infiltrated Troops Out Movement (TOM) and Big Flame and belatedly admitted having had short-term sexual relationships with ‘Mary’ and with three other women he met while on deployment. The impact this had on ‘Mary’ is discussed in detail in her statements to the Inquiry.

After an investigation by Big Flame discovered that Rick Gibson’s identity was fake, activists confronted Gibson with the evidence – the death certificate for the real Rick Gibson – in a pub.

Unbeknown to the activists, Craft and HN244 Angus McIntosh – apparently having been forewarned – were waiting outside in case Gibson faced physical danger.

Although Craft remembered HN297 Richard Clark’s cover identity being compromised, he said that he was not aware of the sexual relationship that was the catalyst for the compromise.

Craft said that SDS management would not have tolerated the risk it would have placed Clark and his family at. This was reiterated in his oral testimony. When Mitting asked Craft directly whether, had this been known, Clark would have faced disciplinary action, including dismissal from the Met, Craft said yes.

However, he added the caveat that this would have been subject to weighing up whether or not this would compromise the security of the unit. Another curious memory lapse was that neither Craft nor McIntosh recalled that they had served together on the SDS, let alone having been outside the pub together.

Craft expressed various concerns about this specific relationship, but expressed remorse towards the women subjected to deceptive relationships only after some prompting.

He also conceded that he should have known, and that he had been naïve in trusting the undercover officers under his command. During his time with the SDS, other SDS officers had sexual relationships; HN21 , HN300 ‘Jim Pickford’ and HN354 Vince Harvey.

Craft said had no recollection about these and denied having overheard ‘banter’ about sexual relationships in the safehouses.

Likewise, Craft had no recollection of the officers who had alleged or confirmed relationships during his time as S Squad chief superintendent; HN106 Barry Tompkins , HN155 ‘Phil Cooper’ , HN12 ‘Mike Blake’ and HN126 ‘Paul Gray’. He claimed not to have heard the rumour that HN67 ‘Alan Bond’ had fathered a child.

In a statement read by their lawyers, Category H core participants argued that it is inherently unlikely that Craft and Angus McIntosh ‘were unaware of the widespread common understanding in the SDS that Richard Clark’s sexual relationships led to the compromise’.

HN304 ‘Graham Coates’, an undercover in the unit at the time, also thought that his managers, including Craft, knew about the sexual relationships.

The submission from lawyers representing the women deceived into these relationships stated:

that the sheer number of significant events attested to by others which Craft claims not to recall itself undermines his evidence.

Positions of influence

Another issue highlighted in the Inquiry’s questioning was that Rick Clark held decision-making posts within TOM, having been branch secretary, branch treasurer, and branch delegate to London. At the national level, he also held the position of London organiser and convenor on the national secretariat.

In his written statement, Craft said:

I did not know that he was prominent in establishing the South-East London branch of TOM, nor did I know anything about his positions of responsibility. I would be very surprised if he did play such a senior role in the group […]

Craft told the Inquiry evidence hearings that he thought Clark was much more junior within TOM. However, later in the hearing, a Special Branch report signed by Craft suggested that he knew Clark had taken the role of London convenor. Craft was unable to explain this or to disagree with the Counsel for the Inquiry summarising the undercover’s position as:

Gibson is an officer who essentially helps to form a branch of TOM, rises all the way through the ranks of the organisation and takes a role in some of the factional in-fighting.

On a similar theme, Craft was also asked about HN353 ‘Gary Roberts’ taking the position of National Union of Students vice-president at Thames Polytechnic. Craft said he had no concerns as Roberts was a ‘particularly able officer’ and commented only that it was ‘interesting’ that he may have influenced decision-making within the NUS as a delegate at the national conferences.

Blair Peach justice campaign

One major event towards the end of Craft’s Special Branch career was the killing of Blair Peach by Metropolitan Police officers during a counter-demonstration to a National Front march through Southall on 19 April 1979.

In evidence, Craft conceded that the Metropolitan Police killed Peach. Still, when asked why Special Branch monitored the justice campaign, he could only suggest that it was because of a potential public-order threat. HN21 , a fully anonymous undercover, thought it may have been Craft who instructed him to attend Blair’s funeral.

However, evidence to the Inquiry, including from Peach’s former partner Celia Stubbs, asserted that there was no public-order threat and pointed out that demonstrations about Peach’s death were completely peaceful.

After the SDS, Craft moved to A Squad (Admin) and Protection in 1979 as a chief inspector. Selected for promotion, he was acting superintendent of operations on B Squad for three or four months between 1979 to 1980 before taking a period of sick leave. He returned to work in the Training and Security Squad as second in command.

In 1980, he became chief superintendent and took over S Squad, saying: ‘The SDS was my biggest responsibility in that role’, although his responsibilities extended to ‘all operational support to Special Branch’.

In his oral testimony, Craft said he made telephone contact, in this role, with a chief inspector or inspector SDS, himself or the S Squad superintendent, alongside occasional visits to the SDS office. Craft was vague about the discussions he had with the SDS officers. He said they would not have discussed where the officers should be deployed, though, and reiterated that this was a matter for C Squad.

Craft then spent three years on B Squad before retiring in 1986, aged 49.

No application was made for a restriction order on behalf of Geoffrey Craft. He had no cover name, and it was decided to publish his real name on 14 November 2017.

Craft submitted two written statements dated 7 December 2020 and 23 February 2022. He appeared as a witness at the Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings on 18 May 2022.